How the World Abandoned Sudan: Power, Fear, and the Threat of Another Genocide in the Power Struggle Between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF)

Original publication by Björn Laurin Kühn, January 11th, 2025.

1 Sudan’s forgotten civil war — Power struggle and ethnic cleansing in West Darfur

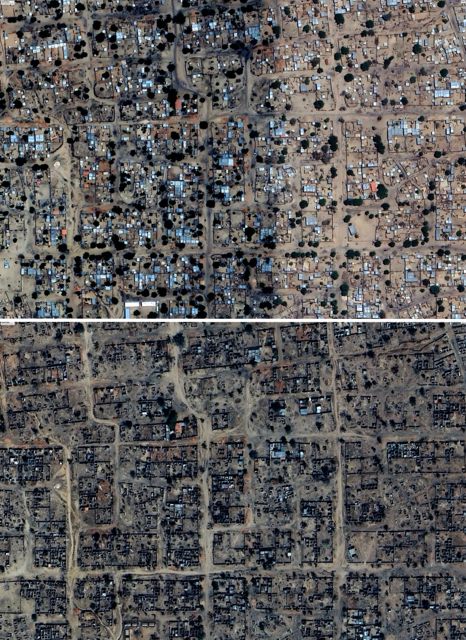

Figure 1: El Geneina, upper picture: 04.2023, bottom picture: 03.2024 (Google Earth Pro, 2024)

There are more than 110 ongoing conflicts around the world (Geneva Academy, 2024). While political leaders and the most prominent media platforms predominantly focus on the conflicts in Ukraine and the Gaza Strip, the conflict in Africa’s third-largest country, Sudan, is often overlooked (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2024). Yet, it threatens to be deadlier than either conflict (The Economist, 2024). Fierce fighting has erupted, particularly in the RSF stronghold in West Darfur, which is on the brink of witnessing a second genocide after the genocidal campaign in 2003-2005 (Human Rights Watch, 2024). To truly grasp today’s conflict dynamics, it is of paramount importance to examine Sudan’s socio-political historical past. Before gaining independence in 1956, the Republic of the Sudan was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt from 1899 onwards (Johnson, 2016, pp. 9-19). However, just two years after Sudanese independence, the country witnessed its first military coup in 1958 when Abdallah Khalil, a retired military officer and sitting prime minister, overthrew his own civilian government to put Sudan under strict military rule (Johnson, 2016, pp. 29-33). What followed in the years after the first military coup can be described as a violent series of military coups: In 1969, Gaafar Nimeiry overthrew the civilian government under Ismail Al-Azhari (Johnson, 2016, pp. 33-34). Subsequently, the next coup happened in 1985, when Gaafar Nimeiry was overthrown by another military officer, namely Abdel Al-Dahab, who then installed a new democratically based government (Johnson, 2016, pp. 70-73). Four years later, in 1989, Omar Al-Bashir took down the civilian government under Sadiq Al-Mahdi and appointed himself as the new head of state (Johnson, 2016, pp. 81-84). Since Omar Al-Bashir knew that his role as the de facto political leader was in severe jeopardy, he decided to entrench his own power through coup-proofing (Vox, 2023). Thus, Omar Al-Bashir surrounded himself with various paramilitary organisations that protected him and remained loyal in case of the emergence of an internal threat (Vox, 2023). With ongoing tensions in South Sudan and the uprisings in the historically neglected region of Darfur in the beginning of the 2000s, Omar Al-Bashir decided to refrain from relying on the SAF but instead decided to arm local militias, particularly the Janjaweed, to crack down on the various uprisings (Totten & Markusen, 2006, pp. 9-24). However, when South Sudan gained independence in 2011, Omar Al-Bashir lost significant influence and was seeking to officially entrench the Janjaweed into his coup-proofing system (De Waal, 2007, pp. 1039-1043). One of the military leaders of the Janjaweed that Omar Al-Bashir trusted the most was Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, usually called Hemedti, who in 2013 became the head of the RSF (Al Jazeera, 2023). As economic and socio-political struggles within the country continued, another uprising emerged in 2018 when the Sudanese government under Omar Al-Bashir allocated up to 70% of the government budget to the security sector, including the RSF and SAF (Vox, 2023). Subsequently, after several months of public demonstrations, the RSF and SAF jointly decided to remove Omar Al-Bashir from power on the 11th of April 2019, ending his 29-year-long rule (BBC, 2019). Only a day after the joint RSF and SAF military coup, Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, a former regional commander in Darfur, officially took charge of the SAF (Afriyie, 2024, pp. 445-457). Nonetheless, despite the removal of Omar Al-Bashir, pro-democracy protests still continued, leading to violent crackdowns on peaceful protests by the SAF and RSF (Afriyie, 2024, pp. 445-457). Subsequently, the international community, inter alia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Ethiopia, and the African Union, pressured the RSF, SAF, and the Sudanese civilian population into accepting a joint power-sharing agreement (Afriyie, 2024, pp. 445-457). According to the officially accepted agreement, a transitional council would be formed, including both military and civilian representatives (Vox, 2023). In order to prevent further tensions, the military would have de facto control for 21 months, and the Sudanese civilian representatives would govern for 18 months (Vox, 2023). However, the institutional design of the transitional council was inherently biased as Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan assumed the role of chair of the council and Hemedti took over the role of vice chair of the council (Afriyie, 2024, pp. 445-457). Despite initial criticism, the transitional council initially acted according to the agreements, installing a new Sudanese prime minister, namely Abdallah Hamdok (Afriyie, 2024, p. 446). However, after multiple staged coups, such as the coup in October 2021, the military ousted Hamdok’s administration in January 2022, leaving power to both the RSF and SAF (Afriyie, 2024, p. 446). Consequently, this led to continuing protests and civil uprisings, ultimately pressuring Hemedti and Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan into another deal, proposing a new civilian-led transitional government by April 2023 (Afriyie, 2024, p. 446). However, one integral aspect of the agreement was the decision that the RSF would need to become part of the SAF. While the SAF wanted this to happen in only two years, the RSF envisaged the transition in ten years (Afriyie, 2024, pp. 446-447). This profound difference led to a significant divergence between Hemedti and Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan. With both the RSF and SAF in positions of potential leadership, tensions escalated into a full-scale civil war in Khartoum on the 15th of April 2023 (Afriyie, 2024, pp. 439-441). Shortly after the conflict erupted, the region of West Darfur quickly became a hotspot for violence between the RSF and SAF, particularly the city of El Geneina (Figures 1 and 2). Furthermore, on the 22nd of April 2023, Arab militias were witnessed mobilising in Shukri, a village close to the A5 road towards the Chadian border (Human Rights Watch, 2024). In order to prevent the conflict between the SAF and RSF from spreading to El Geneina, civil society actors, community elders, and government officials met on the 24th of April 2023 and reached an agreement (Human Rights Watch, 2024). However, the next day fierce fighting erupted between the SAF, RSF, Masalit fighters from self-defence groups, and the Sudanese Alliance of Governor Abakar (Human Rights Watch, 2024). Eyewitnesses reported that RSF fighters repeatedly attacked several Masalit-majority neighbourhoods, including Al-Jamarek, Al-Madaress, Al-Majliss, and various internally displaced persons (IDP) gathering sites, such as the Al Zohra IDP camp that had already been targeted before (Human Rights Watch, 2024; Reuters, 2023). Subsequently, in the following days, RSF and allied Arab militias killed approximately up to 15,000 people who were predominantly Masalit (Le Monde, 2024). Consequently, on June 15th, 2023, tens of thousands of predominantly Masalit tried to flee towards Ardamata in a kilometres-long column, which got intercepted by RSF and local militias, leading to the death of hundreds of individuals (Human Rights Watch, 2024; Sudan War Updates, 2023). Concluding all the depicted information, one may argue that the ongoing conflict in Sudan is of paramount importance not only for its neighbouring African countries but also for the international community at large, given its crucial geostrategic location.

Figure 2: El Geneina, Left Picture: 04.2023, Right picture: 03.2024 (Google Earth Pro, 2024)

2 SWOT and PEST analyses

In order to thoroughly examine the ongoing conflict in Sudan, particularly the socio-political situation in Darfur, this paper will employ both SWOT and PEST analytical frameworks. These methodologies will enable a systematic exploration of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) and the political, economic, social, and technological factors (PEST) of the conflict in Sudan. While the SWOT framework will examine factors at a micro level, the PEST framework will focus on macro aspects to analyse and assess broader socio-political dynamics.

2.1 Strengths: Intra-communal resilience, diaspora assistance, and growing international media awareness

Looking at the overall strengths, one can examine two factors that have shown to influence the alleviation of pertinent issues within the conflict in Sudan and particularly in Darfur. To begin with, despite the fierce conflict, Sudanese women have shown immense leadership and resilience, trying to not only provide for their own families but also look out for their respective communities. Thus, neighbourhood networks, community organisations, and the broader Sudanese feminist movement play a crucial role in the distribution of humanitarian aid (Action Against Hunger, 2024). Hence, these groupings function as the very backbone of Sudanese civilian resilience and national hope for a transition to a more peaceful national period. Furthermore, volunteers from the Sudanese diaspora are also collectively organising mutual aid efforts to provide humanitarian assistance to those in need by providing food, psychosocial services, and shelter opportunities (Inkstick, 2024). Nonetheless, the dependency on the mobilisation of Sudanese women is certainly not something new and has already shown to be highly influential during the downfall of Omar Al-Bashir (Inkstick, 2024). Additionally, the Sudanese youth also play a crucial role in building up intra-communal resilience to alleviate humanitarian distress. Thus, only days after full-scale war broke out, youth established so-called emergency rooms to provide services for people in need (Christian Michelsen Institute, 2023). Furthermore, another strength can be defined as growing, albeit incrementally, international awareness. While the overall international media attention still remains relatively low (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2024), local media outlets and individuals on various social media platforms have tried to increase global societal awareness of the ongoing war and humanitarian distress in Sudan. Consequently, these efforts could lead to an increase in funding and in international societal awareness, and thus to pressure on national governments to actively contribute to alleviating humanitarian distress and ending the war in Sudan. However, given the fact that 90% of Sudanese media outlets have been forced to close down and with 80% of all 18 Sudanese states cut off from the internet and communication services, it becomes increasingly difficult, particularly in rural areas in West Darfur, to receive reliable and unbiased information from the ongoing situation (Free Press Unlimited, 2024; UNESCO, 2024). One of the reasons why international awareness only increases incrementally can be characterised as psychic numbing, which refers to a situation in which international apathy is closely correlated to the increasing number of victims, thus slowing down international responses (Deutsche Welle, 2024). Nonetheless, it simply cannot be denied that international awareness has increased due to local journalists and individuals trying to provide the international community with neutral, reliable, and objective information.

2.2 Weaknesses: Lack of central authority and the total collapse of critical infrastructure in Sudan

Examining the weaknesses, one may amplify the lack of central authority and the total collapse of infrastructure in Sudan. To begin with, given Sudan’s internal power dynamics, the country is mostly divided into SAF- and RSF-controlled regions. Yet, as neither group can claim exclusive central authority to impose order on the country, Sudan is sliding into new rounds of violence that have been structured along ethnic lines, particularly in West Darfur (International Crisis Group, 2024). Furthermore, given the lack of central state authority and the subsequent power vacuum, militias have multiplied. While the RSF and SAF are responsible for the majority of humanitarian atrocities, they are less in control of local militia leaders, thus leading to widespread civilian killings. Before the outbreak of the war, there were less than 20 militia groups (ACLED, 2024). Now there are almost 70 local and regional militias acting against or in cooperation with the main warring parties, ultimately making it more difficult to alleviate humanitarian suffering (ACLED, 2024). Additionally, these militias also tend to act ‘under the radar’, oftentimes committing war crimes that go unnoticed, as can be seen with the conflict in El Geneina, where the local population was terrorised by several militias and the RSF. Finally, due to the lack of central state authority, it also remains increasingly difficult for local and international humanitarian organisations to provide humanitarian aid. Notable examples are instances of the RSF blocking and seizing international humanitarian aid from Doctors Without Borders, ultimately using starvation as a weapon of war (Sudan War Monitor, 2024; OHCR, 2024). Examining the second weakness, namely the total collapse of Sudanese infrastructure, one may argue that the current civil war has left a trail of severe destruction not only affecting civilians directly but also the infrastructure in Sudan. Due to the ongoing conflict, specific areas of infrastructure, such as schools, healthcare facilities, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services, have partially been destroyed. Thus, 10,400 schools have been shuttered, leaving 19 million children out of school (African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies, 2023). Furthermore, approximately 80% of Sudanese hospitals are nonfunctional (African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies, 2023). Besides, approximately 15 million people are in need of WASH services, thus posing a severe risk to public health (African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies, 2023). Finally, the Sudanese Ministry of Higher Education has also noted that 104 governmental and private education centres were impacted by the war and have been either partially destroyed, damaged, or even looted (The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, 2024). Consequently, given the disruption and destruction of vital infrastructure, local and international humanitarian organisations are physically not able to access remote areas, particularly in West Darfur, to help those who are in need.

2.3 Opportunities: Revival of Trumpism and regional cooperation through the African Union (AU)

Given the depicted strengths and weaknesses, one may outline two potential opportunities within the war in Sudan, particularly focusing on the ongoing ethnic cleansing in West Darfur. To begin with, following Donald J. Trump’s victory in the 2024 U.S. elections, questions are being raised about how his administration will respond to the ongoing crisis in Sudan. Given the fact that Trump did not specifically mention Sudan during his last election campaign, one may argue that his first term could give a glimpse into what could be expected in the upcoming 4 years. Thus, Trump’s underlying ‘America first’ paradigm amplifies the need to avoid unnecessary external interference and to stay focused on domestic issues. Therefore, Trump’s administration may only seek to cooperate with Sudan if it serves U.S. foreign interests. This can also be seen within the framework of the Abraham records that the first Trump administration initiated in 2020, ultimately to encourage the Sudanese state to normalise its diplomatic relationship with Israel (Dabanga Sudan, 2024). Subsequently, it is expected that the second Trump administration will refocus on these agreements to achieve stability within the wider region that would serve U.S. interests. Consequently, this may lead to economic support of Sudan but will most likely come as foreign direct investment (FDI) and not as direct state aid. Whether Trump will actively intervene in the conflict by following the Biden administration’s role to act as a mediator between the warring parties remains to be seen in the upcoming months. However, given the ubiquitous Chinese and Russian influence in Sudan, for example, the most recent deal in which the SAF agreed to give the Russian government a Red Sea base in exchange for weapons (The National, 2024), the Trump administration might be following a more proactive role to prevent losing influence in the wider region. Finally, a second opportunity could be multilateral regional cooperation through the AU. Despite being one of the most detrimental conflicts on the African continent in decades, the African Union has largely failed to find the right response to the conflict (Amnesty International, 2024). After the civil war broke out in 2023, the AU’s Peace and Security Council convened a meeting on May 27, adopting a six-element roadmap for the resolution of the conflict (Qiraat African, 2024). Yet, the AU’s roadmap and following negotiation attempts in 2024 largely failed to end the conflict permanently. Consequently, the AU should effectively work together with the UN and regional humanitarian and security actors to achieve regional stability (Institute for Security Studies, 2023). Given the fact that the conditions for the deployment of a multilateral peacekeeping mission by the UN are not fulfilled (Human Rights Watch, 2024), the AU has to push for further multilateral negotiation rounds and ceasefire talks between the warring parties to immediately alleviate the humanitarian distress and prevent another genocide in West Darfur.

2.4 Threats: Genocidal campaigns, widespread famine, and the spillover effects of mass displacement

Figure 3: Outskirts of Adré in eastern Chad, 2021 & 2024 (Sentinel Hub, 2024).

Finally, looking at the threats of the Sudanese conflict, particularly the fierce fighting in West Darfur, one may notice several significant factors. To begin with, the most imminent threat is the occurrence of another wide-scale genocide in West Darfur. The RSF allegedly holds four of the five SAF bases in the Darfur region and is actively besieging the city of El Fasher with heavy military equipment, including tanks (Sudan Tribune, 2024; The Guardian, 2023). While the RSF has been accused of carrying out campaigns of torture and ethnic cleansing in El Geneina (Suppressed News, 2024), the RSF may soon control all of West Darfur, thus significantly increasing the likelihood of further ethnically motivated mass killings (The Guardian, 2023). Additionally, another major threat is widespread famine caused by the ongoing conflict and delayed or even blocked humanitarian support. Thus, there are approximately 26 million Sudanese civilians, more than half of the Sudanese population, who are facing acute hunger, threatening the lives of millions of children who suffer from malnutrition (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2024; United Nations, 2024). Disproportionately affected are IDPs and civilians who remain in the conflict-driven areas of Sudan (OCHR, 2024). Finally, aside from triggering thousands of deaths and widespread famine, the ongoing power struggle between the RSF and SAF also triggered the world’s largest displacement crisis, with 11 million people trying to find refuge (OCHR, 2024). While the number of both IDPs and refugees is rapidly increasing, Sudan’s neighbouring countries may face a significant threat of destabilisation due to the vast number of refugees moving away from the ongoing conflict. This is particularly evident in border towns, such as Adré in eastern Chad (Figure 3), showcasing the rapid expansion of large refugee camps in just several weeks. The conflict between the RSF and SAF has thrown into turmoil a region that has been suffering under record levels of humanitarian stresses. Therefore, even prior to the outbreak of the war, there were more than 13 million people in Sudan and its seven neighbours who were refugees or IDPs. Additionally, more than 40 million people in these countries were facing acute food insecurity and health issues (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2023). Overall, the risk of a regional spillover into other neighbouring countries is high given Sudan’s role at the intersection of the Horn of Africa, the Indian Ocean, and the Arab World (Africa Defense Forum, 2023).

2.5 Political factors: Sudan’s role in the Sahel coup belt and foreign multilateral interference

Within the PEST analysis framework, political factors stand out as particularly influential in shaping the dynamics of the overall crisis. To begin with, being located in the Sahel region of the coup belt, Sudan has a long history of coups d’état, thus oftentimes being categorised as a coup laboratory (Institute for Security Studies, 2020). In its modern history, Sudan has witnessed thirty-five coups d’état, placing it at the forefront of countries in the region with the highest frequency of military upheavals (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023). Of the thirty-five coups d’état, only six were successful, while twelve failed and seventeen were stopped in advance (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023). While the origin of such an extensive history of military upheavals is multifaceted, the reoccurring problem seems to be rooted in the Sudanese military governance system, exemplified by the most recent coup. Furthermore, being closely intertwined with the first factor, since the beginning of the colonial influence in Sudan, the country, and especially West Darfur has experienced wide-scale foreign interference from countries such as Egypt and Russia, which further destabilises the political climate (Paradigm Shift, 2024). Being motivated by factors such as strategic importance, economic interests, and power influence, various countries build up connections with powerful individuals and groups to further their own interests. Overall, these intertwined political factors—Sudan’s role within the African coup belt and the repeated occurrence of foreign interference—create a highly destabilised environment.

2.6 Economic factors: Implications on economic activity and humanitarian dependence

Examining the economic factors, one may argue that the war’s far-reaching implications on Sudan’s economic activity and its humanitarian dependence significantly influence the country’s development prospects and hope for a stable and functioning national economy. To begin with, in 2023, Sudan’s economy shrunk by 40% due to the onset of the armed conflict between the SAF and RSF and is predicted to continue shrinking by approximately 28% in 2024 (Africa News, 2024). Given the critical damage of Sudan’s industrial sector, the backbone of its economy, and the destruction of critical infrastructure, Sudan’s foreign trade and exports, particularly to its neighbouring countries, have significantly decreased (Africa News, 2024). Additionally, the Gezira scheme close to Khartoum (Figure 4) and the gold mines in Darfur have been turned into battlegrounds, further intensifying Sudan’s economic despair (World Food Programme, 2024). Hence, Sudan’s civil war has devastated its economic capabilities, causing an estimated loss of approximately 14 billion Euros (Policy Center for the New South, 2024). Consequently, given the situation of Sudan’s economy and the lack of central state authority, Sudan has increasingly become dependent on humanitarian assistance. Yet, as international awareness is rather low and external humanitarian assistance has become scarce, mutual aid efforts have significantly increased. Regions such as Darfur have been particularly affected, as income sources have been destroyed and violence continues, thus further intensifying the overall dire situation. Overall, Sudan’s civil war has left its economy in ruins, leading to general dependence on humanitarian aid that often gets blocked or used for other purposes. Consequently, this further intensifies humanitarian distress and political instability, particularly in the historically neglected region of Darfur.

Figure 4: The Gezira Scheme (October 2021-November 2024), (Sentinel Hub, 2024)

2.7 Social factors: The dimensions of multi-ethnicism and multiculturalism in Sudan

Sudan is home to an estimated population of 50 million people, encompassing over 500 ethnic groups (Central Intelligence Agency, 2024). While Sudanese Arabs constitute the majority of Sudan’s ethnic groups at about 70% of the population (The Conversation, 2024), the country is also home to a significant minority of diverse African ethnic groups, such as the Nuba, Fur, Beja, Fallata, and the Masalit (Central Intelligence Agency, 2024). Besides, while approximately 97% of Sudan’s population adheres to Sunni Islam, the remainder follows either African traditional religions, animist beliefs, or Christianity (United Nations Development Programme, 2008). Nonetheless, while the distinct languages, cultural identities, customs, and traditions contribute to the rich ethnic diversity of Sudan, it also presents various challenges, creating social cleavages not only between Arab and non-Arab ethnic groups but also within Arab ethnicities. This can be exemplified by the very conflict between Hemedti and Al-Burhan. Thus, many Darfurian Arabs who comprise the military base of the RSF are in personal conflict with the Khartoum ruling class, which consists of Sudan’s riverine Arabs that have controlled Sudan since its independence (The Jamestown Foundation, 2024). However, this conflict is not new and is rooted in historical conflicts that date back to the Mahdist rule from 1885-1899 (The Jamestown Foundation, 2024). While the conflict between different Sudanese Arab ethnicities is particularly pertinent to grasping the institutional rivalry between the RSF and SAF, the violence directed at non-Arab ethnic groups stems from a different source. Thus, with the growing influence of the Tajamu al-Arabi in the 1980s, clashes over land ownership between Arab and non-Arab ethnicities erupted in Darfur (The Jamestown Foundation, 2024). Subsequently, some of the Darfurian non-Arab ethnicities, such as the Fur, Masalit, and the Zaghawa, united to form a rebellion in 2003. Consequently, the Sudanese government under Omar Al-Bashir relied on the Janjaweed, who pursued a brutal crackdown of the protests, leading to murder, rape, and ultimately genocide, thus triggering the creation of intra-communal psychological trauma and widespread distrust between ethnic groups (Shoib et al., 2022). These historical wounds were reopened immediately after conflict erupted between the RSF and SAF and spilt over into West Darfur in 2023 (BBC, 2023). Therefore, it cannot be denied that the dimensions of multi-ethnicism and multiculturalism play a dominant role within the conflict in Sudan, particularly in the ethnic cleansing campaigns of the RSF in West Darfur.

2.8 Technological factors: The external weaponisation of Sudan’s civil war – ‘Guns for gold’

Finally, examining the technological factors, the ongoing war in Sudan has become a focal point for external countries and non-governmental entities seeking to further their own strategic interests. Subsequently, one implication of this power play can be exemplified through the external weaponisation of the warring parties. Therefore, particularly regional countries, such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia, but also countries such as Russia, China, and France (War Noir, 2024), are fuelling Sudan’s war through past and present deliveries of weapons either directly into Sudan or through Chad (Amnesty International, 2024; Al Jazeera, 2024; Foreign Policy, 2023; The Washington Post, 2024). Despite the UN arms embargo on Darfur, which can generally be assessed as being too narrowly focused and only seldomly implemented in an adequate manner (Amnesty International, 2024), large quantities of manufactured weapons and military equipment find their way into Darfur and other regions of Sudan. The incentive for external powers to engage in weapon deliveries is usually Sudan’s richness in natural resources, such as gold. While oil has historically played a crucial role in Sudan’s export economy, after the secession of South Sudan in 2011, the Sudanese state lost three-quarters of its oil reserves, thus giving more importance to precious metals, such as gold (Patey, 2024). Sudanese smuggled gold usually gets shipped to the UAE, where it then enters the global market, ultimately financing the war of the RSF against the SAF (African Defense Forum, 2024). Just a year before the war broke out, the UAE imported 39 tonnes of gold from Sudan, which is worth more than 1.9 billion Euros (Arms Technology, 2024). While the current gold import statistics are unavailable, direct exports of gold and other precious metals to the UAE have largely continued after the war had started in 2023. In return, under the guise of humanitarian assistance, the UAE actively provides regular military support to the RSF’s stronghold in West Darfur via an airport in Amdjarass in Northern Chad (Figure 5-6) (Al Jazeera, 2024; Euro News, 2024; FlySkyUA Official, 2023).

Figure 5: Amdjarass International Airport (January 2024-November 2024), (Sentinel Hub, 2024)

Figure 6: Ilyushin IL-76 at Amdjarass International Airport (October 10, 2024), (Sentinel Hub, 2024)

Additionally, aside from interference through imports from sovereign states, the black market of military equipment and advanced weaponry has been thriving since the war began in 2023. Hence, due to high demand not only from the RSF and SAF but also from local militias and civilians who wish to protect themselves, there has been a rapid increase in the circulation of weapons within Sudan. Yet, already before the war there were an estimated 5 million illegal arms in the hands of Sudan’s 48 million citizens, further intensifying the overall situation in Sudan (Radio France Internationale, 2023). Overall, Sudan’s external and private weaponisation further destabilises the wider region and significantly contributes to the ongoing civil war.

3 Conclusion: Strategic pathways for peace and security – Short- and mid-term strategic priorities

Concluding all the mentioned aspects of the SWOT and PEST analyses, one may outline several short-term (1-year span) and mid-term (5-year span) recommendations to address key issue areas within the Sudanese conflict. To begin with, examining the short-term recommendations, for many years, Sudan witnessed the presence of a multinational peacekeeping force. From 2007 to 2020, the UN and AU jointly led a hybrid peacekeeping presence in West Darfur after the genocidal campaign against non-Arab minorities (United Nations, 2020). Subsequently, this was followed by a UN-led political mission, originally established to provide support during Sudan’s transition to democracy, which was suddenly suspended in February 2024 (Africa News, 2024). Consequently, there has been no regional or multilateral presence in Sudan that is responsible for the protection of civilians and ultimately to ensure that all of the responsible parties abide by international law. Yet, the lack of international media attention and the reduced international presence in Sudan will only further serve to embolden the warring parties to commit atrocities. Furthermore, it should be amplified that most stakeholders are relatively pessimistic that the RSF and SAF will agree to another UN-led peacekeeping mission, which is a substantial precondition for UN peace operations. Hence, similar to the recommendations of the UN independent fact-finding mission to Sudan (International Peace Institute, 2024), the first short-term strategic priority should be to diplomatically push for an AU-led peacekeeping mission. Besides, the mission could be financially supported by the UN through resolution 2719, which allows for a greater humanitarian impact (The Conversation, 2024; United Nations, 2023). Ultimately, such a mission structure would ensure a higher probability that the warring parties would consent to international assistance (The Conversation, 2024). Nonetheless, it is of utmost importance that such an AU-led peacekeeping mission also has a political role to ensure that the mission has some political leverage to efficiently achieve its goals. Subsequently, given the successful creation of such an AU-led peacekeeping mission, a second strategic short-term priority should be a swift deployment to protect the civilian population within vulnerable cities in West Darfur, such as El Fasher. After the El-Geneina massacre in 2023, the RSF strategically attacked other large cities in West Darfur, home to thousands of non-Arab communities that have become victims of ethnically targeted violence. North Darfur’s capital, El Fasher, has been under siege since May 2024 and is facing a grave humanitarian crisis with thousands of civilians being trapped inside the urban centre (ABC News, 2024). However, despite demands of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to end the siege of El Fasher in June 2024, the RSF blatantly ignored it and continued to attack various parts of the city, threatening the lives of thousands of civilians (Sudan War Monitor, 2024). Thus, El Fasher remains the last stronghold of the SAF in West Darfur, functioning as a vital strategic location to control the wider area (The New Humanitarian, 2024). Moreover, a third short-term strategic priority should be the creation of humanitarian “safe zones” that would ensure the protection of the civilian population. Consequently, this would also enable international organisations to provide civilians with food and medical supplies. Therefore, such humanitarian “safe zones” should particularly be created in the Darfur region, where humanitarian distress and the likelihood of ethnically targeted violence are the greatest. Furthermore, a fourth short-term strategic priority should be to extend the UN arms embargo to all of Sudan. Thus, since 2004, when Arab Janjaweed fighters carried out a genocidal campaign in Darfur, the UN had put in place an arms embargo solely targeted at the Darfurian region (Voice of Africa, 2024). However, as seen by the widespread external influence of third parties, such as the UAE and the Russian Federation (The Guardian, 2024; The Jamestown Foundation, 2024), it is of paramount importance to extend the UN arms embargo to the whole country. Consequently, this would ensure a complete restriction on the sale, supply, and transfer of military weaponry, ammunition, and equipment to any warring party within the entire country. Finally, a fifth short-term strategic priority should be to continue negotiations for an immediate ceasefire agreement. So far, peace talks have widely failed to come to any agreement between the warring parties. The most recent negotiations convened in August 2024 in Geneva, including Egypt, the UAE, the AU, and the UN as observers. However, while the RSF sent a delegation, the SAF refused to take part in the negotiations, leading to no direct contact between the two warring parties (United States Institute of Peace, 2024; Wilson Center, 2024). Therefore, to improve the chances of success in future negotiations, peace talks must be more inclusive, and a priori establish concrete roles and responsibilities for both the RSF and SAF. Otherwise, the latter will not agree to a ceasefire agreement, thus significantly decreasing the probability for sustainable peace within Sudan (Wilson Center, 2024). Looking at the mid-term strategic priorities, joint sustainable efforts will be necessary in order to stabilise the wider region, ultimately to ensure a long-lasting peace between the warring parties. To begin with, the first mid-term strategic priority should be to ensure sustainable and continuous access to humanitarian aid. The brutal conflict since April 2023 has left almost 25 million people, i.e., more than half of Sudan’s population, in need of humanitarian aid (International Rescue Committee, 2023). Therefore, ensuring efficient access to humanitarian aid, particularly in the historically neglected areas in Darfur, will be of paramount importance. Furthermore, the second mid-term strategic priority will be the structural rebuilding process of Sudan, once a peace agreement has been concluded between the warring parties. Therefore, to ensure the continuous access to humanitarian aid, the transport system, healthcare facilities, and educational facilities have to be rebuilt. Moreover, the third mid-term strategic priority will be a disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR) campaign targeted at the warring parties and various local militias that are involved in the war. Generally, DDR campaigns are crucial components of both the immediate stabilisation of conflict-driven societies as well as their long-term development (United Nations, 2020). Consequently, this ensures the security and stability in post-conflict areas and specifically focuses on the reintegration of RSF and SAF fighters who have radicalised themselves during the ongoing conflict. To support the latter, the fourth mid-term strategic priority will be the creation of a reconciliation program, similarly to the program that was put in place after the Rwandan genocide in 1994 (Ted-Ed, 2023). In essence, such a reconciliation program would enable Sudan to acknowledge its past, including the intercommunal violence directed towards non-Arab ethnic groups. Additionally, it would enable justice to be done through special tribunals or local courts, such as the Gacaca courts that were used in Rwanda, and support victims and the wider society to move beyond its historical past towards a more united Sudanese state (United Nations Development Programme, 2021). Ultimately, this could also potentially weaken the cleavage between the different ethnicities in Darfur. Finally, the fifth mid-term strategic priority will be the gradual transformation to civilian governance, independent from interference from the SAF or RSF. Despite the failure of the civilian government under Abdallah Hamdok, establishing a stable and democratic civilian government remains essential. Therefore, a successful transition to a civilian democratic government would not only prevent military interference in state affairs but also help pave the way for a more democratic and peaceful future for the Sudanese state.

4 Bibliography

ABC News. (2024, October 6). Inside Sudan’s El Fasher, a city under siege amid a civil war. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/629gv

ACLED. (2024, May 21). Q&A: Sudan’s broken hopes. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/h4y6r

Action Against Hunger. (2024, October 24). From violence to resilience. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/jnpmw

Africa Center for Strategic Studies. (2023, May 2). Sudan conflict straining fragility of its neighbours. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/3cbvz

Africa Defense Forum. (2023, May 23). Sudan conflict threatens to ensnare neighbors. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/tajpn

Africa News. (2024, August 13). Sudan’s economy contracts 40% as war rages. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/fc02k

Africa News. (2024, August 13). UN ends political mission in Sudan. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/pazsi

African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies. (2023, November 24). Sudan’s war and its devastating impact on infrastructure. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/b3i8a

African Defense Forum. (2024, February 13). Smuggled gold fuels war in Sudan, UN says. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/kspf2

Afriyie, F. A. (2024). Sudan: Rethinking the conflict between Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). India Quarterly, 80(3), 439–456.

Al Jazeera. (2023, April 16). Who is ‘Hemedti’, general behind Sudan’s feared RSF force? Retrieved from https://t1p.de/9ykln

Al Jazeera. (2024, January 24). UAE denies sending weapons to Sudan’s RSF paramilitary: Report. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/6pzu7

Amnesty International. (2024, April 12). Sudan: One year since conflict began, response from international community remains woefully inadequate. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/founy

Amnesty International. (2024, July 25). New weapons fuelling the Sudan conflict. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/gnnjf

Amnesty International. (2024, November 14). Sudan: French-manufactured weapons system identified in conflict – new investigation. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/abhet

Arms Technology. (2024, September 6). ‘Guns for gold’: who is complicit in Sudan’s brutal war? Retrieved from https://t1p.de/oba4u

BBC. (2019, April 15). Sudan coup: Why Omar al-Bashir was overthrown. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/bqeyi

BBC. (2023, November 8). Sudan conflict: Thousands flee fresh ethnic killings in Darfur. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/pbk09

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2023, August 17). Sudan’s conflict in the shadow of coups and military rule. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/7jrjy

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024, September 11). Conflict, hunger, and famine in Sudan. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/qyhj9

Central Intelligence Agency. (2024, November 6). The World Factbook – Sudan. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/mh6x8

Christian Michelsen Institute. (2023, April 13). War, resilience, and rooting. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/z7aln

Dabanga Sudan. (2024, November 7). How will Trump’s return to the White House impact Sudan? Retrieved from https://t1p.de/4vn74

De Waal, A. (2007). Darfur and the failure of the responsibility to protect. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 83(6), 1039–1054.

Deutsche Welle. (2024, June 14). Why is the world ignoring the Sudan civil war? Retrieved from https://t1p.de/9fzq2

Euro News. (2024, June 19). Sudan accuses UAE of fueling war in the country. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/ssu0f

FlySkyUA Official. (2023, July 8). Fly Sky Humanitarian aid [Picture on Twitter]. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/nkhee

Foreign Policy. (2023, July 12). How Sudan became Saudi-UAE proxy war. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/m5p7p

Free Press Unlimited. (2024, November 6). Support for Sudan media forum’s ‘Silence kills’ campaign. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/yodv7

Geneva Academy. (2024). Today’s armed conflicts. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/egx3g

Google Earth Pro. (2024, October 29). El Geneina (Al-Jabal neighbourhood), upper picture: 04.2023, bottom picture: 03.2024. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/4334a

Google Earth Pro. (2024, October 29). El Geneina (Center), left picture: 04.2023, right picture: 03.2024. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/4334a

Human Rights Watch. (2024, May 9). Sudan El Geneina timeline. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/k9jy0

Human Rights Watch. (2024, May 9). Sudan: Ethnic cleansing in West Darfur. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/lxe51

Human Rights Watch. (2024, October 24). UN, African Union should take bold action to protect Sudanese civilians. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/x8qt2

Inkstick. (2024, March 20). The crisis in Sudan and the unseen resilience of mutual aid. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/6ap6b

Institute for Security Studies. (2020, July 31). Sudan, a coup laboratory. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/9jk24

Institute for Security Studies. (2023, September 7). Sudan exposes the AU’s weak response to humanitarian crises. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/bvdr5

International Crisis Group. (2024, January 9). Sudan’s calamitous civil war: A chance to draw back from the abyss. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/nwxwi

International Peace Institute. (2024, September 30). More peacekeeping for Sudan? Retrieved from https://t1p.de/qca41

International Rescue Committee. (2023, April 18). Fighting in Sudan: What you need to know about the crisis. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/3xacb

Johnson, D. H. (2016). The Root Causes of Sudan’s Civil Wars: Old Wars and New Wars. Boydell & Brewer.

Le Monde. (2024, January 23). Massacres in Darfur town have killed up to 15.000, UN report says. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/fcbm8

OCHR. (2024, October 17). Sudan faces one of the worst famines in decades, warn UN experts. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/jvlcj

OHCR. (2024, June 26). Using starvation as a weapon of war in Sudan must stop: UN experts. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/buvta

Paradigm Shift. (2024, June 1). Sudan foreign involvement: Proxy wars and economic interests. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/ca4c3

Patey, L. (2024). Oil, gold, and guns: The violent politics of Sudan’s resource re-curse. Environment and Security, 2(3), 412-430.

Policy Center for the New South. (2024, October 24). The ongoing war in Sudan and its implications for the security and stability of the Horn of Africa and beyond. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/1xp2t

Qiraat African. (2024, August 15). What is hindering the African Union in the Sudan war? Retrieved from https://t1p.de/tgku0

Radio France Internationale. (2023, August 31). In Sudan’s east, murky arms trade thrives as war rages. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/98u3b

Reuters. (2023, December 28). The Sudanese commanders waging war on the Masalit. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/25oob

Sentinel Hub. (2024, December 3). Amdjarass International Airport (January 2024-November 2024). Retrieved from https://t1p.de/fjpmk

Sentinel Hub. (2024, December 3). Ilyushin IL-76 at Amdjarass International Airport (October 10, 2024). Retrieved from https://t1p.de/fjpmk

Sentinel Hub. (2024, December 3). The Gezira Scheme (October 2021-November 2024). Retrieved from https://t1p.de/fjpmk

Sentinel Hub. (2024, October 29). Refugee camp at the outskirts of Adré in eastern Chad from 2021-2024. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/fjpmk

Shoib, S., Osman Elmahi, O. K., Siddiqui, M. F., Abdalrheem Altamih, R. A., Swed, S., & Sharif Ahmed, E. M. (2022). Sudan's unmet mental health needs: A call for action. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012), 78, 103773.

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. (2024, April 22). How (not) to talk about the war in Sudan. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/iz3x4

Sudan Tribune. (2024, November 20). The United Arab Emirates has warned the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) it may cut off support if the paramilitary group fails to seize control of El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, a source close to the Chadian presidency told Sudan Tribune [Video file on Twitter]. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/2f7c8

Sudan War Monitor. (2024, August 29). RSF still blocking aid for starving children. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/p1t49

Sudan War Monitor. (2024, October 28). UN Security Council offers tepid response to Sudan crisis. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/wx4bz

Sudan War Updates. (2023). Retrieved from https://t1p.de/80f1q

Suppressed News. (2024, June 6). One of the countless crimes of the Rapid Support Forces [RSF] militia against innocent people of Sudan [Video file on Twitter]. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/pgnfi

Ted-Ed. (2023, June 27). What caused the Rwandan genocide? – Susanne Buckley-Zistel. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/crqxo

The Conversation (2024, September 18). Sudan’s civilians urgently need protection: the options for international peacekeeping. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/9yki7

The Conversation. (2024, April 25). Sudan’s civil war is rooted in its historical favouritism of Arab and Islamic identity. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/z6wb9

The Economist. (2024, August 29). Why Sudan’s catastrophic war is the world’s problem. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/stc1w

The Guardian. (2023, November 21). Sudan’s cycle of violence: ‘There is a genocide going on in West Darfur’. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/c9pcv

The Guardian. (2024, May 24). It’s an open secret: the UAE is fueling Sudan’s war – and there’ll be no peace until we call it out. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/duium

The Jamestown Foundation. (2024, July 8). Russia switches sides in Sudan war. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/ftn3b

The National. (2024, June 5). Sudan army set to give Russia Red Sea base in exchange for arms. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/srcm5

The New Humanitarian. (2024, November 27). Inside the battle for El Fasher: “Innocent lives are lost every day”. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/sx96j

The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy. (2024, April 15). A war for Sudan’s identity: The loss and destruction of culture and heritage. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/4mumr

The Washington Post. (2024, October 15). Sudan’s civil war fueled by secret arms shipments from UAE and Iran. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/fk4om

United Nations Development Programme. (2008, June 30). Sudan overview. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/pggjv

United Nations Development Programme. (2021, July 9). Truth and Reconciliation the way to chart South Sudan’s path forward. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/rprz2

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2024, May 22). Sudanese media and media freedom organizations call for continued support. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/qiii8

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2024, February 7). UN relief chief tells media “very, very difficult to get attention to Sudan”. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/lnngk

United Nations. (2020, April 14). Disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR). Retrieved from https://t1p.de/9xnvr

United Nations. (2020, December 31). UNAMID ends its mandate on 31 December 2020. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/4w4ow

United Nations. (2023, December 21). Resolution 2719 (2023). Retrieved from https://t1p.de/fpphq

United Nations. (2024, August 6). Warning 26 million people facing acute hunger in Sudan, senior world food programme official tells Security Council. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/u7l59

United States Institute of Peace. (2024, September 4). Without Sudan’s warring parties in Geneva, what’s next for peace talks? Retrieved from https://t1p.de/1y41l

Voice of Africa. (2024, September 11). International arms embargo on Darfur renewed as fighting rages. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/4umy8

Vox. (2023, May 26). Sudan’s conflict, explained. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/ccbod

War Noir. (2024, November 21). Sudanese Forces carried out an attack on Rapid Support Forces positions [Video file on Twitter]. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/hmanl

Wilson Center. (2024, October 31). Sudan’s ceasefire talks: What has been missing thus far? Retrieved from https://t1p.de/ct3lf

World Food Programme. (2024, April 13). Economic fallout of Sudan war deepens hunger crisis for millions. Retrieved from https://t1p.de/sira0

Figure 6: Ilyushin IL-76 at Amdjarass International Airport (October 10, 2024), (Sentinel Hub, 2024)