NATO, Russia, and the Eastern Flank: A historical and geopolitical overview

By Aldo Carano

The myth of the “broken promise”

A myth characterizes the very beginning of NATO-Russia relations, before the birth of the Russian Federation itself: the supposed promise to the Soviet Union, on behalf of the George H.W. Bush Administration, not to expand the eastern borders of the Atlantic Alliance. Supporters of such a view quote the words of US Secretary of State James Baker about “no extension of NATO’s jurisdiction for forces of one inch to the east.”[1]

However, this narrative is not consistent for two reasons. The first of these is related to the historical and geopolitical context at the beginning of the 1990s. The main focus of the group of countries dealing with the future of Eastern Europe—the so-called “Two plus Four group”, made up of East and West Germany plus the United States, France, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom—was the reunification of Germany. The long-term path of the Atlantic Alliance was not in discussion. Former USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev himself declared in 2014 that “The topic of NATO expansion was never discussed. It was not raised in those years.”[2] Early in the talks, Soviet leaders insisted that a unified Germany never become part of NATO, though they eventually accepted Germany’s right to self-determination. Similarly, the United States stepped back from Baker’s initial language on not expanding “NATO’s jurisdiction” in East Germany. In the end, the treaty recognizing German unification that the Two Plus Four powers signed in the summer of 1990 stipulated that only German territorial (i.e., non-NATO) forces could be based in East Germany, while Soviet forces withdrew. After that, only German forces assigned to NATO could be based there, not foreign NATO forces. The treaty does not mention NATO’s rights and commitments beyond Germany.[3]

Secondly, the rapid dissolution of the Warsaw Pact (July 1991), the collapse of the Soviet Union (December 1991), and the birth of many sovereign states completely changed the equation of NATO’s Eastern Flank. Even if a commitment of non-enlargement towards the East was made, the post-1991 events produced a dramatic change of circumstances.

Perspectives of cooperation: The Founding Act

The 1990s were crucial years for the development of NATO-Russia relations. With the 1991 Strategic Concept and the establishment of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council, NATO stressed the importance of partnership, cooperation, and a new dialogue with Eastern partners. Dialogue, sharing information, and consultations was finally preferable to deterrence. The launch of the Partnership for Peace (PfP) constitutes an example of such a new relationship.[4] The Partnership for Peace was based on the dual necessity of providing stability, especially in the new-born countries, and securing the future of young democracies. New partners could enjoy bilateral cooperation with the Atlantic Alliance, setting shared priorities, areas of interest, and pace. Since 1994, tens of countries joined the PfP, including Russia, Ukraine, and Georgia.[5]

The dialogue with Russia was formalized by the NATO-Russia Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security (for here on referred to as the Founding Act) on 27 May 1997.[6] The Founding Act is the fundamental document to understand where and how NATO and Russia cooperated and may cooperate in the future, and also why the actions of the Russian Federation in Ukraine in 2014 and in 2022 constitute a violation of mutual commitments. At the end of the 1990s, the two parties needed to establish a permanent framework of relations and cooperation, especially considering the upcoming accession of Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary (1999). Criticism from Russia towards the enlargement of the Atlantic community was emerging, and the relations between Moscow and Brussels needed a clear path for dialogue. Signed in Paris, the Founding Act outlines NATO and Russia’s shared commitments to democracy, rule of law, and respect for the sovereignty of all States. It is divided into four parts[7]:

1. Principles: importance of Euro-Atlantic security, crucial importance for the role of the OSCE and the Helsinki Final Act, response to new risks and challenges, such as aggressive nationalism, proliferation of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons, terrorism, persistent abuse of human rights.

2. Mechanism for Consultation and Cooperation, the NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council: the constitution of a Permanent Joint Council as a framework of consultation, coordination, and (a very ambitious point for further developments) joint actions.

3. Areas for Consultation and Cooperation: areas such as security and stability, conflict prevention and preventive diplomacy, crisis management, exchange of information, arms control issues

4. Political-Military Matters: NATO’s pledge to Russia comes from this section, “The member States of NATO reiterate that they have no intention, no plan and no reason to deploy nuclear weapons on the territory of new members, nor any need to change any aspect of NATO’s nuclear posture or nuclear policy.” While NATO’s promise was fulfilled, Russian behaviour was contrary to that outlined in the Founding Act, as I will eventually discuss.

The Founding Act was also a way to address Russian criticism of the extension of the Atlantic community. As former US ambassador to NATO Kurt Volker said, “It was trying to reassure Russia that, look, we’re going to bring some new countries into NATO, but this does not mean we are against you, we’re not threatening you in any way.” [8]

In the spirit of the NATO-Russia Founding Act, the cooperation between the two parties led to the Rome Declaration, which was established, during the Rome Summit on 28 May 2002, and the NATO-Russia Council (NRC).[9] The NRC created a permanent forum where Russia was not a guest anymore (i.e., in ad hoc NATO-Russia summits), but a full member of a permanent structure for dialogue. In this context of partnership and for the following years, Russia supported the NATO-led, UN-mandated International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), supporting the transit of non-military equipment through Russian territory. Russia also offered its support to the Atlantic Alliance during Operation Active Endeavour, the NATO operation in the Mediterranean against terrorism, and Operation Ocean Shield in the African Horn.[10]

The analysis of the myth (or misunderstanding) of the broken promise of non-expansion of NATO towards Eastern Europe and the actual framework of NATO-Russian relations set by the Founding Act may help to understand how the narrative supported by Russian President Vladimir Putin is partial and incorrect. During his well-known speech at the Munich Security Conference on 10 February 2007, his manifesto against the role of the United States and the West in the international arena, Putin touched also the point of NATO enlargement to Eastern Europe, quoting a speech by Manfred Woerner (Secretary General of NATO from 1989 to 1984) to support the thesis of the broken promise of non-expansion[11]:

[Woerner] said at time that “the fact that we are ready not to place a NATO army outside of German territory gives the Soviet Union a firm security guarantee. Where are these guarantees?

Similar to Baker, Woerner was referring to the former Eastern Germany, without any prejudice against the accession of Eastern European countries, and in a phase of negotiations before the complete agreement on German reunification. In other words, Putin was extending an informal and conversational speech about German reunification to Eastern Europe as whole, ignoring the final agreement and the real commitments taken by the Atlantic Alliance and Russia as outlined in the NATO-Russia Founding Act, which did not pose any restriction to further membership. Putin’s speech in Munich is the symbol of a period of tensions in NATO-Russia relations.

The following year, 2008, was marked by major contrast between the behaviour of the Atlantic Alliance and Moscow. During the 2008 Bucharest Summit (2–4 April), NATO welcomed Georgia and Ukraine’s aspirations for membership by supporting their applications for the Membership Action Plan (MAP), the next step for the two countries on their way to membership. At the end of the Summit, Allies declared that Georgia and Ukraine “will become members of NATO”.[12] Vladimir Putin, invited to the Summit, expressed the strongest possible opposition to the two countries’ membership in NATO. Four months after the Summit, Russia launched its first attempt to enlarge its so-called sphere of influence in the post-Soviet space: Russian forces illegally entered into Georgian territory and occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia in August. The following step for the Kremlin’s revisionism would be undertaken, on a major scale, in Ukraine in 2014. In both the crises, the issue of NATO membership was a core issue.

The first Ukrainian crisis and the Dual Track policy

Russia’s illegal and illegitimate annexation of Crimea, as well as its hostile actions in Eastern Ukraine in March 2014, constitute a qualitative leap in Russia’s more assertive posture in Eastern Europe, in continuity with the invasion of Georgia in 2008. Alongside the UN Charter and the NATO-Russia Founding Act, the Russian government violated the Budapest Memorandum of 1994, regulating the relations between Russia and Ukraine mediated by the US and the UK. In exchange for the renunciation of the 4,000 Soviet nuclear weapons stockpiled in its territory, Russia recognized the independence, territorial integrity, and security of Ukraine.[13] Undertaking military actions and annexing parts of Ukrainian territory in 2014 and, more dramatically, launching a full-scale military invasion in 2022, Moscow violated the core points of the Memorandum:

- To respect the independence and the full sovereignty of Ukraine.

- To refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine.

- To provide assistance if Ukraine should become the victim of aggression or object of a threat of aggression.[14]

NATO at first condemned Russian actions in 2014, and later, in April, Allies suspended military and civilian cooperation. However, in order to leave room for negotiations, NATO decided to maintain the NATO-Russia Council, although its summits had been suspended in the aftermath of the Russian occupation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia in 2008. The illegal actions in Ukraine were also accompanied by hostile actions towards the Alliance itself: the Russian air force has undertaken, since 2014, military flights along NATO’s Eastern borders: 39 encounters between NATO and Russian forces, with a potential risk of escalation, were a direct consequences of such behaviour, in addition to violations of Alliance air space.[15]

This environment led the Alliance, under Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, to adopt a “dual track” deterrence/dialogue policy.[16] To respond to Russia’s actions, NATO launched the Readiness Action Plan (RAP) at the Wales Summit in September 2014, in order to adapt to the new context requiring more activism along Eastern borders. The turning point of such deterrence and security policy was the 2016 Warsaw Summit.[17] Allies established the enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in the Northeast and the Tailored Forward Presence (TFP) in the Southeast.[18] In particular, the enhanced Forward Presence has the crucial task of guaranteeing the security of the most exposed States: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, which are patrolled by four multinational battlegroups, led by the UK, Canada, Germany, and the US.

NATO ENHANCED FORWARD PRESENCE - source: NATO, NATO’s military presence in the east of the Alliance - https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_136388.htm

The Warsaw Summit and the establishment of the two Forward Presences are part the largest reinforcement of the Eastern Flank before 2022.

In the spirit of the “dual track” policy, NATO has since pursued dialogue with Russia, especially in the sector of arms control. This is the case for the INF Treaty, signed in 1987 by US President Reagan and Soviet President Gorbachev.[19] The INF is a milestone for arms control, since it freed Europe from the Euromissiles, ballistic and cruise missiles that could travel between 500 and 5,500 kilometres. However, since 2013, Russia has developed, produced, tested, and deployed, especially in its exclave of Kalingrad, a new intermediate-range missile known as the 9M729, or SSC-8.[20] The 9M729 is mobile and easy to hide. It is capable of carrying nuclear warheads and it can reach European capitals in few minutes. NATO had played a crucial role in asking Russia for clarification and compliance with the INF.[21] In 2017, Russia admitted the presence of missiles, but claimed that they complied with the treaty. In 2018, Allies denounced Russia’s unilateral breach, urging the Russian government to resolve the issue. However, the breach led to the US withdrawal from the Treaty.

NATO’s response to the Russian war against Ukraine: From the March Summit to the new Strategic Concept

NATO has reacted decisively to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which unfolded on 24 February 2022. Despite the criticism that NATO is “a braindead organization” given by French President Emmanuel Macron in a well-known interview with The Economist magazine in 2019, NATO has possessed the strength to condemn Russian actions, speak with a single voice, and reinvigorate the transatlantic alliance between the US and Europe, including among European member states and the European Union. The ad hoc NATO summit of 24 March 2022, convened in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, is not only the most important summit after the Cold War but also a marker of a drastically changed international order, which requires a more united and bolder Atlantic community.

Let us examine the leaders’ statement in detail.[22] With the core purpose of the Alliance at stake—i.e., the security of its members—the first part of the statement deals with common values: democracy, rule of law, the UN Charter, sovereignty of all states, solidarity with Ukraine. It recognizes Allies’ security in multiple areas, embracing every sector of the international arena: conventional, cyber, chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats.[23] Russia is defined as a threat to international security and stability[24]: this passage is fundamental to understand the nature of the international system we live in, which is strongly characterized by great power competition and revisionist actors (like Russia and China) breaching common rules and proposing their own “parallel” international order. In this sense, it encourages China, a traditional partner of Russia and a major “revisionist” power, not to support Russia in evading measures taken to punish its actions in Ukraine, like sanctions and restrictions.[25]

Moreover, the communiqué includes a reference to two interesting articles of the NATO Treaty. Article 5 is mentioned as a guarantee of security and mutual solidarity among allies; the reference to Article 10, regulating the possibility of new members, is a way to highlight the “open door policy” of NATO towards other countries (a reference to Ukraine, but also to Sweden and Finland, which presented their applications at the summit)[26] and to provide a further response to Russian claims about the “broken promise”.

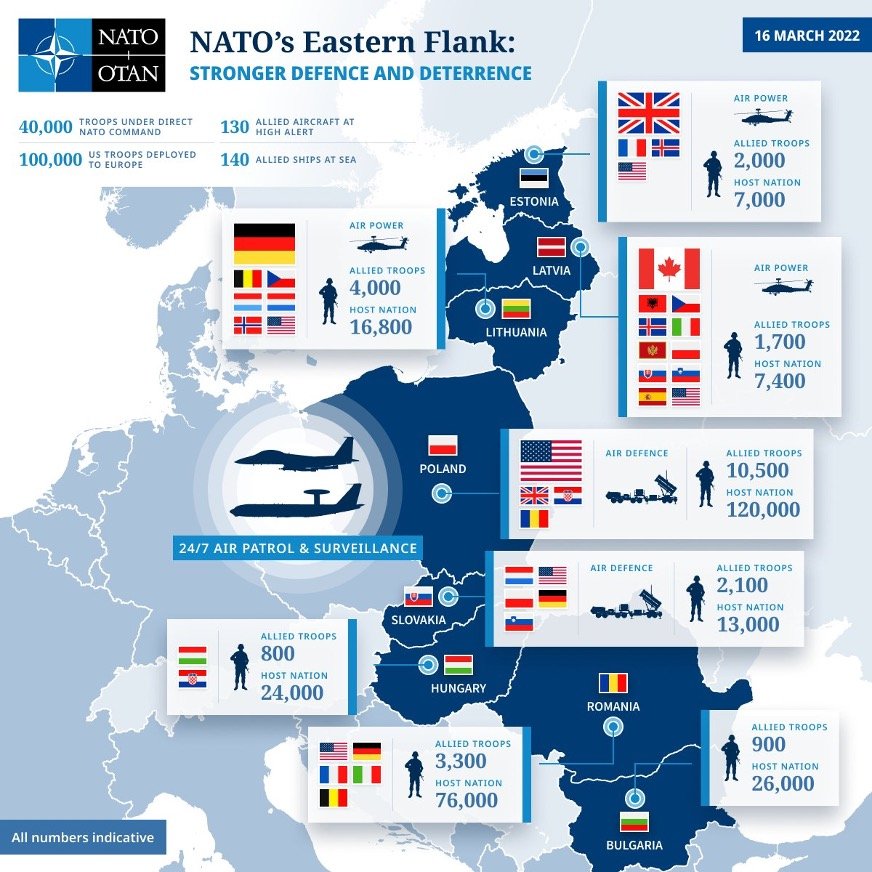

The statement substantially confirmed the measures adopted on 16 March 2022 by the Supreme Allied Command to strengthen the Eastern Flank in order to prepare the Alliance for any eventuality.[27] The US will deploy 100,000 troops in Europe, while new troops will be posed under NATO command. Bearing in mind the continuous violations of air space occurring since 2014, Allied Command imposed 24/7 air patrol and surveillance of the Eastern Flank. The battlegroups already present along the Eastern Flank were reinforced, while some countries like Poland and Slovakia were provided with advanced air defence systems.

THE STRENGHTENING OF THE EASTERN FLANK IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE RUSSIAN AGGRESSION AGAINST UKRAINE - source: source: NATO, NATO’s military presence in the east of the Alliance - https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_136388.htm

Finally, the communiqué introduces the incoming Summit of Madrid of 28–29 June 2022, where the new Strategic Concept was presented and approved.

NATO’s new Strategic Concept provides a clear set of guidelines for the Alliance in the medium term. The 2022 Strategic Concept calls for a 360-degree renewal of NATO.[28] The document identifies many challenges (Russia, China, terrorism, Middle East, cyberspace, climate change) and a vast set of responses.[29] However, here, I will focus only on Russia. Analysing the strategic environment in which NATO will operate in the coming years, Russia is the first challenge identified. In contrast to the last Strategic Concept, Allies can no longer consider Russia as a partner, since it began a war of aggression against Ukraine and brought all-out war back to Europe, contributing to a broader deterioration of Euro-Atlantic peace and security.[30] NATO’s military posture has been adjusted accordingly, moving from enhanced forward presence to forward defence.[31] This implies a far more robust pre-deployment of US, Canadian, and Western European military capabilities along NATO’s eastern flank, including command and control structures, personnel and equipment.[32] Moreover, due to continuous threats coming from Russian officials about a nuclear response even to economic sanctions or other non-military measures, NATO’s defence plans will increasingly focus on “high-intensity, multi-domain warfighting against nuclear-armed peer-competitors. In addition, the document moves arms control, disarmament, and non-proliferation from the core task of cooperative security to that of collective defence.[33] Moreover, the document confirms NATO’s commitment to a dual track policy: collective defence shall be accompanied by a “meaningful and reciprocal political dialogue”.[34]

Conclusions and recommendations

The Atlantic Alliance was born as a transatlantic community of countries sharing the same values and willing to find a common path of security and cooperation. In many phases of the Cold War, the security and integrity of Europe seemed at risk, and NATO played a major role as a security guarantor. Following the Cold War, NATO recognized that any lasting and peaceful international order cannot exclude Russia from dialogue and cooperation. For this reason, NATO’s decision to maintain its openness to cooperation with Russia, despite its numerous and serious violations of the Founding Act, and to pursue dialogue together with deterrence should be viewed as a positive step. However, to guarantee NATO countries’ security and to support Ukraine, it is also necessary to act firmly.

First of all, the Alliance should (as it is doing) set some red lines: nuclear threats cannot be tolerated. Any use of weapons of mass destruction should find an assertive and proportionate answer. Security in Eastern Europe may be pursued through the massive reinforcement of the Eastern Flank. The US plan to send US $33 billion in aid to Ukraine announced by President Joe Biden (which Congress later raised to US $40 billion)[35] goes in such direction. Such efforts make the Alliance safer by empowering allies to do more to defend common interests in Europe. The more the US and NATO do to strengthen the Eastern Flank, the better collective deterrence, and the possible response to Russia, will be. As the Baltics are the first line of defence, in accordance with NATO’s new posture and to reduce the risk of aggression, we need to improve air and defence missiles there. Moreover, the current phase of Russia’s war against Ukraine relies on artillery: an increase of artillery and ammunition is essential.[36] The 2022 war also proved the importance of NATO’s intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (ISR) sector, especially in the first days, when Russia was attempting to undermine the Ukrainian government and the chain of command: an effective response on behalf of Allied intelligence that prevented such operations. The importance of funding and strengthening deterrence is stressed by the proposed US “Baltic Defense and Deterrence Act”.[37] The Act aims to improve long-range precision fire systems and capabilities, integrated air and missile defense, command, communications, and ISR of the Baltic countries, bolstering the long-term security of NATO allies.

Moreover, even if Ukraine cannot join NATO, the Alliance’s Open Door policy should continue. In this sense, the membership of Sweden and Finland will be a game-changer for the Alliance. In the case of Finland in particular, its accession would add 830 miles of frontier between NATO and Russia in the East. This could help us to ease Russia’s pressure on the Baltics.

The 2022 Strategic Compass offers a clear picture of the path. Combining conventional deterrence with nuclear and increasing the Alliance’s conventional strength along the Eastern Flank, supported by preparedness in hybrid and cyber warfare and intelligence, may help to deter Russia from attacking NATO Allies. Such deterrence, combined with open channels for negotiation, may help the Atlantic Alliance to face the most vital challenge after the Cold War.

About the Author

Aldo Carano is a second-year master’s degree student in European and International Studies at the School of International Studies of the University of Trento. From September–December 2022, he will work as an intern for the Italian embassy in Ukraine. His main research interests are transatlantic relations and NATO, US–EU relations, and bilateral relations between the US and European partners. He is passionate about the history of international relations, diplomacy, and geopolitics. He is a Junior Fellow at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) and a member of AESI (European Association of International Studies). During an AESI conference at the Library of the Italian Parliament, he discussed the role of NATO for European security.

*The opinions expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of any organization(s) affiliated with them.

Notes

[1] J. Masters, “Why NATO Has Become a Flash Point With Russia in Ukraine,” Council on Foreign Relations, Backgrounder, last updated 20 January 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/why-nato-has-become-flash-point-russia-ukraine?utm_source=dailybrief&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=DailyBrief2022Jan24&utm_term=DailyNewsBrief.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid,

[4] NATO, “Relations with Russia,” last updated 14 July 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_50090.htm

[5] G. Cella, Storia e geopolitica della crisi ucraina (Roma: Carrocci editore, 2021), p. 269.

[6] Amy Mackinnon, “The NATO-Russia Founding Act Is Hanging by a Thread,” Foreign Policy, 14 July 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/14/nato-russia-founding-act/.

[7] NATO, “NATO-Russia Founding Act,” 27 May 1997, https://www.nato.int/cps/su/natohq/official_texts_25468.htm.

[8] Mackinnon, “The NATO-Russia Founding.”

[9] NATO, “Relations with Russia.”

[10] Ibid.

[11] Cella, Storia e geopolitica, p. 287.

[12] NATO, “Bucharest Summit Declaration, Issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Bucharest on 3 April 2008,” last updated 5 July 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_8443.htm.

[13] Cella, Storia e geopolitica, p. 295.

[14] Ibid., p.297.

[15] Ibid., p.300.

[16] NATO, “Relations with Russia.”

[17] Ibid.

[18] NATO, “NATO’s military presence in the east of the Alliance,” last updated 8 July 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_136388.htm.

[19] NATO, “NATO and the INF Treaty,” last updated 2 August 2019, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_166100.htm.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] NATO, “Statement by NATO Heads of State and Government, Brussels, 24 March 2022,” last updated 4 July 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_193719.htm.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] NATO, “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept,” 29 June 2022, https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Alessandro Marrone, “NATO’s New Strategic Concept: Novelties and Priorities,” Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), 8 July 2022, https://www.iai.it/it/pubblicazioni/natos-new-strategic-concept-novelties-and-priorities.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] NATO, “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept.”

[35] Alan Fram, “Democrats want to boost Biden Ukraine aid plan to near $40B,” ABC News, 10 May 2022, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/wireStory/democrats-boost-biden-ukraine-aid-plan-40b-84599765.

[36] Lauren Speranza, Ben Hodges, and Krista Viknins, “Bolstering the Baltics: Accelerated Security Assistance,” CEPA, 11 May 2022, https://cepa.org/bolstering-the-baltics-accelerated-security-assistance/.

[37] Congress of the United States of America, Baltic Defense and Deterrence Act S.3950 - Baltic Defense and Deterrence Act, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/3950/text?r=3&s=1.