NATO’s policy towards women’s inclusion

By Karolina Siekierka. Originally published on March 16th, 2024 on LinkedIn.

INTRODUCTION

Gender imbalance is a widespread problem that needs to be addressed. Women constitute around half of the population, but they are still underrepresented in fields that have been traditionally dominated by men, such as security, defence, and military. Women face obstacles and discrimination due to stereotypes about their social roles and personality traits. Such stereotypes lead to – in my opinion – a wrong conclusion that women don’t belong in, for example, the military, and they cannot be ministers of armed forces or defence. Ultimately, these stereotypes put women lower in the social hierarchy.

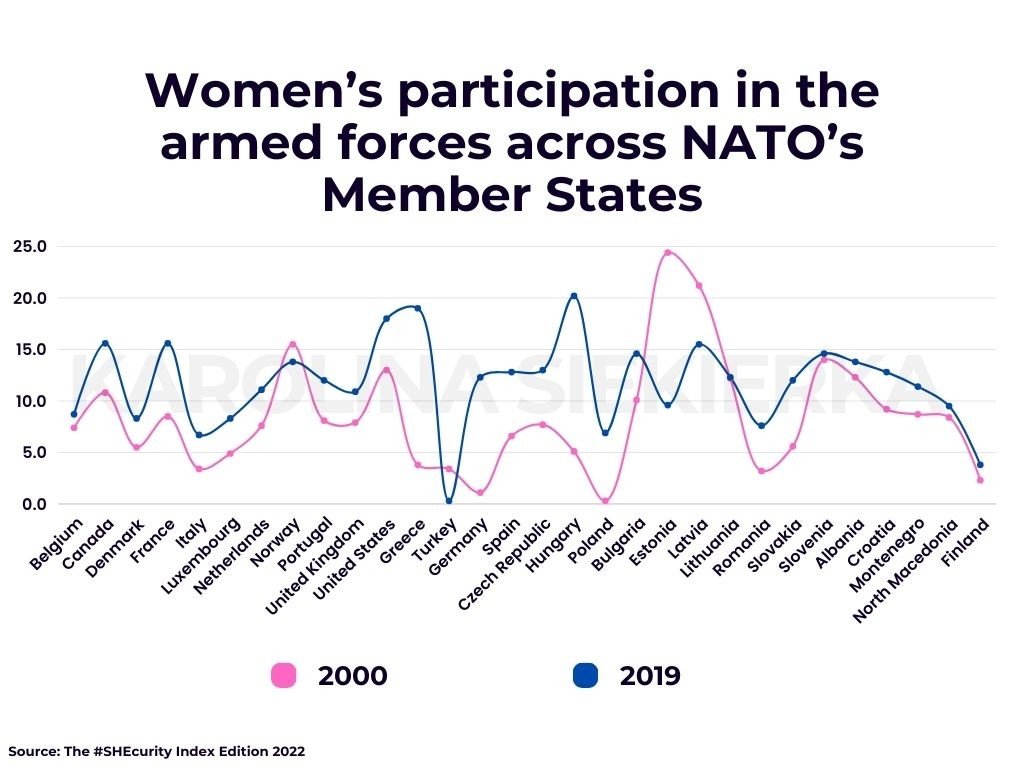

Today, women constitute around 11% of NATO’s military personnel, with no country reaching 20% of female presence. Although the proportion of women in the male-dominated security sector has increased in the past two decades, the number of women operating in this domain is still too low to bridge the gender gap. Based on the progress made between 2009 and 2018, it is estimated that NATO’s member states will take 465 years to achieve gender equality.

Gender equality is a crucial component of a country’s security and stability. However, it is often overlooked in those sectors. Women are, however, at the core of security, and NATO has undertaken various activities, policies, and initiatives to achieve gender equality.

While analyzing NATO’s efforts and policies towards women’s inclusion, it is essential to keep in mind a member state’s individual approach, its declarations, and demographic statistics. NATO’s policy results from international regulations and recommendations, such as the UN, and negotiations between member states. It is also essential to note that NATO and the EU work closely together. Among NATO’s 32 member states (Sweden officially joined NATO on March 7th, 2024), 23 countries are members of the European Union. The 23 EU states can pursue their political and military interests through differently tasked institutions.

THE MAIN IMPORTANCE OF FEMALE PARTICIPATION

There are several reasons why it is important to have women participate in the defence and security sector, as well as in conflict prevention.

The United Nations states that female officers often have access to populations and locations that are typically off-limits to men. Men soldiers are often associated with violence, which can limit their ability to communicate and build trust with local communities. When women soldiers are involved, there is a greater chance of improved relations between the military and local communities, as women are better able to overcome social barriers, avoid cultural taboos, and maintain cultural sensitivity. Furthermore, women usually refuse to use excessive force and are less likely to escalate tensions. Additionally, female soldiers’ participation might lead to fewer misconduct complaints, as well as improve local communities’ perception of armed forces. Lastly, a visible presence of female soldiers might also empower women in host communities.

Women’s participation in military, defence, and security sectors results therefore in greater trust and integration with the local communities, allows women to gather important information about potential security risks, and increases situational awareness of the environment in which the military operates.

All the above leads to improved operational efficiency.

GLOBAL STANDARD: UN WOMEN, PEACE AND SECURITY AGENDA

NATO’s approach towards women’s inclusion is based on the UN Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Agenda, launched in 2000 with the adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325. The Agenda is followed by 9 additional resolutions.

Previously, men were predominantly the only focus in armed conflict. However, the introduction of the WPS Agenda marked a significant shift for states to acknowledge the diverse roles women play in the security and peace processes, including as victims, recruiters, combatants, caregivers, informants, or activists.

The UN Women, Peace and Security Agenda features four pillars, including:

the role of women in conflict prevention;

women’s participation in peacebuilding;

protection of the rights of women and girls during and after conflict;

women’s needs during repatriation, resettlement, rehabilitation, reintegration, and post-conflict reconstruction.

Women, Peace and Security resolutions can be grouped into two categories. The first focuses on the need for women’s active and effective participation in peacemaking and peacebuilding. The second focuses on preventing and addressing conflict-related sexual violence.

NATO developed its first policy around the Women, Peace and Security Agenda in December 2007.

NATO’S PATH TOWARDS GENDER EQUALITY

NATO has been committed to promoting gender equality since the 1960s. The first conference on the status and employment of women within the Alliance’s military forces was held in Copenhagen in 1961 and was organised by senior female officers. This conference initiated discussions on the status, conditions of employment, and career possibilities for women in the armed forces of the member states of the Alliance.

Fifteen years later, in 1976, NATO’s Military Committee established the Committee on Women in the NATO Forces, a consultative body consisting of national delegates from each member state. Its role was to advise NATO’s leaders on critical issues and policies affecting women in the NATO Forces. It also supported the member states with guidance on gender-related and diversity issues. In 2009, the committee changed its name to the Committee on Gender Perspectives.

The 1961 conference and the Committee on Women in the NATO Forces initiated changes and transformation within NATO. However, the Alliance’s transformation began much later, in the 2000s. Between 2000-2010, the Alliance debated the topic rather than acting on it.

In 2002, during the Prague Summit, member states were tasked to recommend ways of improving gender balance within International Staff and International Military Staff, which led them to the establishment of the Gender Balance and Diversity Task Force in 2003. The Task Force’s role was to coordinate policies, identify barriers, and promote activities to build a diverse and inclusive workforce.

In 2007, NATO adopted a policy around the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda, which focused on how gender perspectives apply in operational contexts and paved the way for further consideration of a gender perspective within the Alliance.

In 2010, during the Lisbon Summit, NATO’s member states created the first Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security policy to support the implementation of the WPS policy. It supports the commitment made by the Allies to further advance gender equality and integrate gender perspectives in all that NATO does, building on the progress made since the creation of NATO’s policy on Women, Peace and Security. The Action Plan was revised and updated in October 2021, it reaffirms NATO’s commitment to advancing gender equality and integrating gender perspectives at every level.

In 2012, NATO created the position of Secretary General’s Special Representative for Women, Peace, and Security. It was made permanent in 2014.

Since 2018, NATO revised the Women, Peace and Security policy and introduced its core principles:

integration – “gender equality must be considered as an integral part of NATO policies, programmes and projects”;

inclusiveness – “representation of women [at all levels] across NATO and in national forces is necessary to enhance operational effectiveness”;

integrity – “systemic inequalities are addressed to ensure fair and equal treatment of women and men Alliance-wide”.

In 2015, NATO launched the Women’s Professional Network and Mentoring Program. That same year, the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which serves as a blueprint for peace and prosperity. It was at this time that NATO increased its efforts towards women’s inclusion and gender equality.

The following year, the Alliance established the NATO Civil Society Advisory Panel on Women, Peace and Security. Its primary task is to promote collaboration with citizens in advancing the WPS Agenda and creating an inclusive security environment. The NATO Civil Society Advisory Panel comprises 24 civil society experts who are representatives of various civil society organisations across the Alliance, global partners, and conflict-affected regions. They possess extensive knowledge of issues related to the WPS Agenda and hold monthly meetings.

NOW: THE 2022 STRATEGIC CONCEPT

The 2022 Strategic Concept, adopted during the Madrid Summit, is the first strategy to call for tangible action. It highlights the importance of investing in and promoting the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda across all of NATO’s core tasks. The Alliance aims to integrate gender perspectives into its political and military structures, with a focus on: (i) deterrence and defence, (ii) crisis prevention and management, and (iii) cooperative security. Gender Advisors are involved at all levels of NATO’s military structures, including in operations and missions. Additionally, the decision-makers of the 2022 Strategic Concept have emphasized that the Alliance will continue to promote gender equality as a reflection of its values.

At the 2023 Vilnius Summit, the commitment to promoting gender equality by integrating the WPS Agenda across all three core tasks was reaffirmed. This integration is expected to be achieved in NATO’s activities, everyday work, missions, and operations. The Allies also agreed to review and update NATO’s WPS Policy, which supports the 2022 Strategic Concept’s goal of improving effectiveness in a changing security environment.

CONCLUSION

Gender equality has a significant impact on the security and defence sector, as it can affect the stability of the world.

NATO has been committed to promoting gender equality by creating policies and programs that promote women’s inclusion and integration of gender perspectives at every level. While these efforts have resulted in a positive trend, there is still much work to be done. The starting point is to ensure women’s safety in the military and defence sectors.

Research and monitoring can demonstrate the benefits that countries gain from women’s inclusion in the military, defence, and security sectors.

SOURCES:

Resolution 1325 (2000) Adopted by the Security Council at its 4213th meeting, on 31 October 2000, https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/SC_ResolutionWomenPeaceSecurity_SRES1325%282000%29%28english_0.pdf

The 2022 Strategic Concept, NATO, June 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf

The #SHEcurity Index 2020, #SHEcurity, 2020, https://shecurity.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SHEcurity-Index-final.pdf

The #SHEcurity Index. Edition 2022, #SHEcurity, 2022, https://shecurity.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/SHEcurity_2022_dataset_final.pdf

The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2023, NATO, 2024, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/3/pdf/sgar23-en.pdf

Vilnius Summit Communiqué, NATO, July 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_217320.htm

Women, Peace and Security, NATO, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_91091.htm

(Photograph on the cover is: “A female member of the NATO KFOR Joint Enterprise for Kosovo in February 11, 2010. REUTERS/Srdjan Zivulovic”