Greyzone Lawfare: Russia and the Voyages of the SPARTA IV

By Jack Crawford, Dr Giangiuseppe Pili, and Nick Loxton. Originally published on 13 September 2023 by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI).

Russia’s likely use of the SPARTA IV, an alleged civilian vessel, to transport military materiel from Tartus, Syria to its port in Novorossiysk is yet another example of Moscow’s penchant for manipulating international law to satisfy its wartime agenda.

Less than a week after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu announced that his government would be utilising its power granted by the 1936 Montreux Convention to severely restrict the passage of military and auxiliary vessels through the Bosporus Strait.

This closure should have prevented the movement of wartime vessels through the Bosporus, preventing illicit redeployment of any military materiel. However, as in the case of the SPARTA IV (IMO: 9743033), certain Russian vessels appear to continue regularly transiting the Bosporus with military materiel, in breach of international law.

Using a diverse range of data sources, analytical techniques and intelligence methods for accurate data analysis, this open source intelligence (OSINT) investigation unearths the truth behind Russia’s attempt to manipulate international law to sustain its unjustified invasion of Ukraine.

To and from Russia, with Love

Automatic identification system (AIS) data provided by Geollect, a close partner of RUSI’s Open Source Intelligence and Analysis (OSIA) research group, and satellite imagery sourced by OSIA from Planet Labs, Maxar Technologies and Airbus Defence and Space confirms the SPARTA IV’s voyages between the ports of Tartus, Syria and Novorossiysk, Russia, and seemingly identifies some of the vessel’s intended cargo.

Figure 1: The SPARTA IV’s journey between Tartus and Novorossiysk

Credit: AIS data provided by Geollect, RUSI OSIA

In 2023, the SPARTA IV has completed at least six voyages between Russia’s military ports in Tartus, Syria and Novorossiysk, Russia:

14 January 2023: The SPARTA IV’s first voyage from Tartus to Novorossiysk of 2023 began. After 11 days of sailing, it arrived in Novorossiysk on 25 January, where it stayed for 22 days before embarking on its return voyage.

1 March 2023: The SPARTA IV again departed from Tartus and arrived in Novorossiysk five days later. On 30 March, it left the port to return to Tartus.

8 April 2023: The SPARTA IV’s next voyage began, arriving in Novorossiysk on 15 April. It remained in port for 21 days before sailing back to Tartus on 6 May.

16 May 2023: The SPARTA IV’s fourth departure from Tartus toward Novorossiysk began. It arrived on 6 June and stayed until 15 June, when it left for the return voyage and arrived back in Tartus on 21 June.

15 July 2023: The ship was imaged by a high-resolution satellite tasked by Planet Labs. The resulting images likely show the ship unloading military material in Novorossiysk after another journey from Tartus.

10 August 2023 (estimated): The SPARTA IV made a return trip to Tartus that was unable to be corroborated by AIS data. The vessel had a significant period of AIS darkness lasting for 292 hours off Lemnos in the Aegean Sea from 3 to 15 August. This signified a change in tradecraft, using much longer periods of AIS darkness to conceal movements. During this period of darkness, satellite imagery confirmed the SPARTA IV in the Tartus port from at least 7 to 10 August, before it sailed back toward Novorossiysk.

Figure 2: 292 hours of AIS darkness.

Credit: AIS data provided by Geollect, RUSI OSIA

Critically, on each of these visits, the SPARTA IV only docked in Russia’s naval base terminals, despite claims from the vessel’s owner that it carries commercial goods.

Figure 3: The SPARTA IV in Russia’s military ports in Tartus (top) and Novorossiysk (bottom)

Credit: AIS data provided by Geollect, RUSI OSIA

A Trojan Seahorse

Russia has consistently used the SPARTA IV as a reliable go-to vessel for sensitive maritime logistical operations.

The SPARTA IV’s construction, certifications and capacity make it an excellent transit vessel for large military materiel, and it maintains reputational and business indicators of this behaviour.

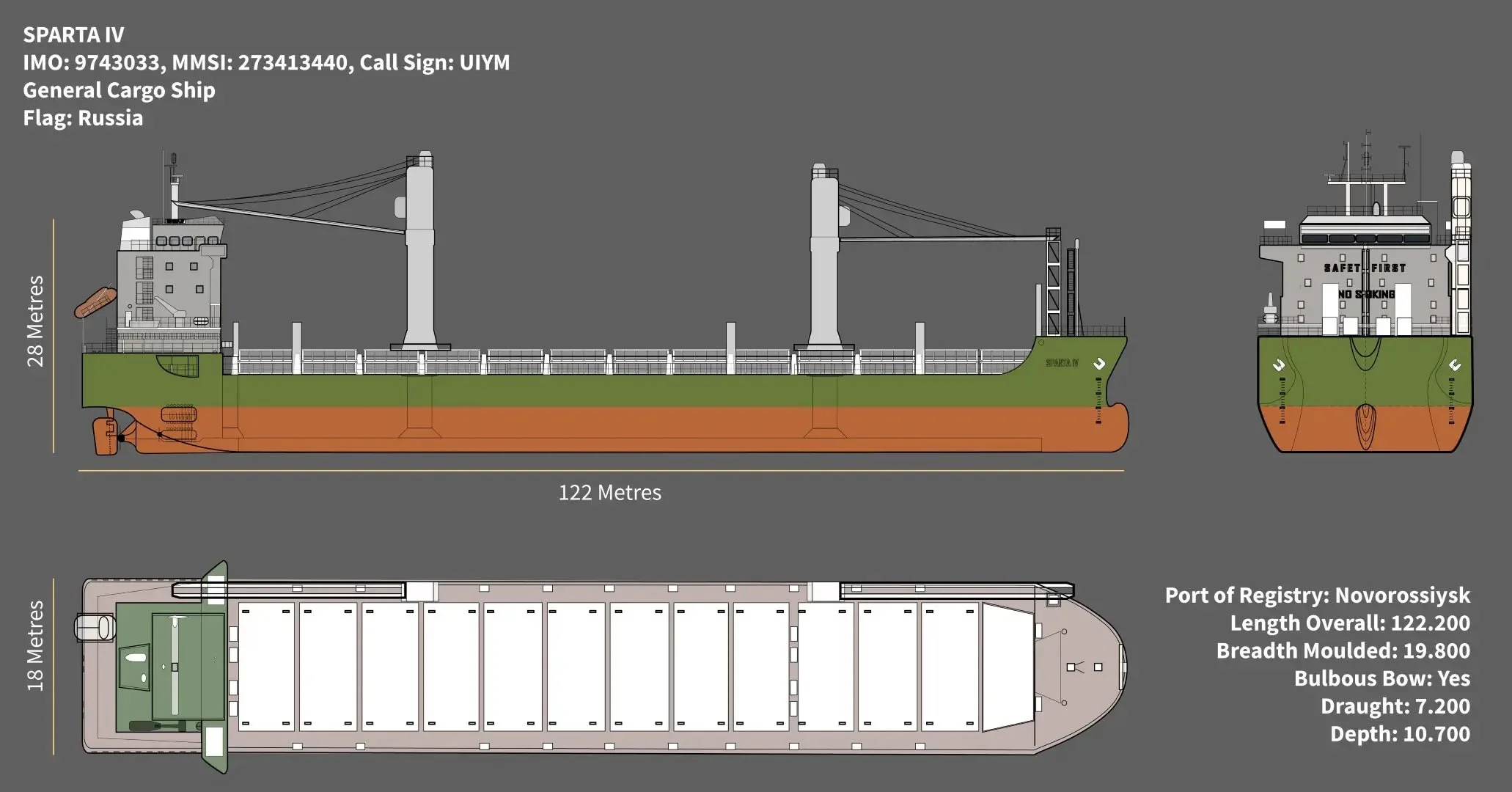

Figure 4: The SPARTA IV

Credit: Dr Giangiuseppe Pili, RUSI OSIA

The vessel is a Russian-flagged general cargo ship weighing 8,870 deadweight tonnes and measuring 122 metres in length by 18 metres in breadth that can reach 14 knots. Its volumetric capacity, its two cranes capable of lifting up to ‘55 tons’, and the overall displacement imply that the ship could easily transport heavy military goods, such as battlefield T-90 tanks deployed in Syria on behalf of the Russian government.

For example, high-resolution satellite imagery over Tartus from 26 February 2022 seems to show 17 vehicles with measurements (approximately 8 m in length by 2.5 m in width) compatible with those of a KAMAZ-5350 tactical truck.

The KAMAZ-5350 appears to measure 7.85 m in length, 2.5 m in width and 3.29 m in height, and has a volume of 64.56 m3. A refrigerated container of 40 tons measures 5.450 m (length), 2.285 m (width) and 2.160 m (height), for a volume of 26.89 m3. The ship can move up to 44 refrigerated containers with a total volume of 1,183 m3, equivalent to over 18 KAMAZ-5350s.

More recently, the SPARTA IV appeared to be loading or unloading dozens of military pieces in Tartus in early August.

Figure 5: Rendering the SPARTA IV’s cargo capacity

CreditDr Giangiuseppe Pili, Oboronlogistics website, RUSI OSIA

Before its current route between Tartus and Novorossiysk, the SPARTA IV lived up to the claim it can ‘walk across three seas’, transporting cargo for Russia through the Arctic, Baltic and South Asian regions. Essentially, if the Russian Ministry of Defence needed maritime logistics somewhere, the SPARTA IV appeared nearby.

Treacherous Ties

The SPARTA IV’s engagement in military transport comes as no surprise; the ship’s ownership structure includes sanctioned Russian defence companies and ties to a preeminent Russian politician.

Oboronlogistics LLC, a Moscow-based company allegedly created to oversee logistics for the Russian Minstry of Defence, is the group owner of the SPARTA IV. The company has been sanctioned by the UK, the US, Canada, Australia and Ukraine for aiding Russia’s 2014 and 2022 invasions of Ukraine. Notably, Oboronlogistics’ website features a video of the SPARTA IV loading military cargo.

The SPARTA IV is directly operated, managed and owned by the Novorossiysk-based SC-South LLC, an Oboronlogistics affiliate which is sanctioned by the UK, Ukraine and the US for delivering maritime goods on behalf of the Russian Ministry of Defence.

Another Oboronlogistics subsidiary, OBL-Shipping LLC, is the SPARTA IV’s technical manager. One of OBL-Shipping's former shareholders was the Chief Directorate for Troop Accommodations JSC, the CEO and director of which was Timur Vadimovich Ivanov, Russia’s deputy defence minister. Ivanov is allegedly ‘responsible for the procurement of military goods and the construction of military facilities’, and has been sanctioned by the EU for financially benefiting from Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Uncharted Waters?

As it continues to unfold, the case of the SPARTA IV reveals Russia’s continued willingness to bend international law and to prioritise military logistics over adherence to international agreements. The SPARTA IV is much more than a cargo vessel and is not operating alone; other vessels with similar patterns of life and ownership structures continue to illegally transit the Bosporus, likely carrying Russian military materiel into the Black Sea. These ships must and can be stopped.

Reporting on the SPARTA IV underscores OSINT’s ability to identify breaches of international law almost instantaneously, offering an opportunity for observation and identification to align with political will from Western governments to enforce compliance in real time.

This article was updated on 26 September 2023 to correct the description of Timur Vadimovich Ivanov.