National Plans for Defence Spending

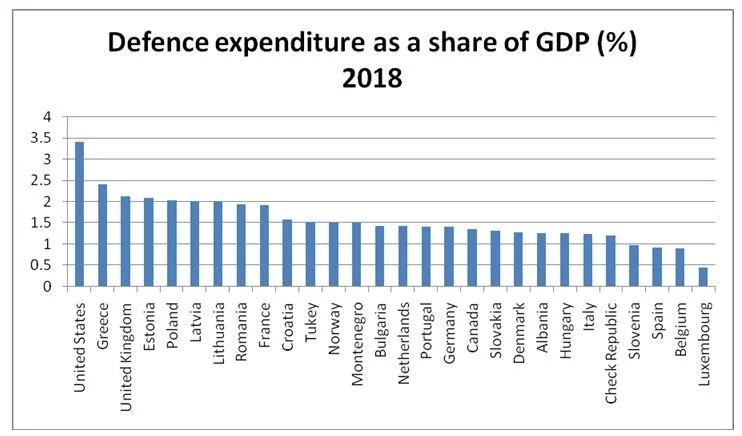

As NATO’s greatest responsibility is to prevent conflict and maintain peace, the Alliance set a goal for its members to spend at least 2% of GDP on defense at the 2014 Wales Summit. Since then, all NATO members have increased defense spending, but according to the 2018 NATO report, only seven of 29 allies are currently meeting the recommended spending target of 2% of GDP. Only six European countries, Greece, the UK, Estonia, Poland, Latvia, and Lithuania, meet the 2% threshold, which has been the main focus and criticism of US President Donald Trump, who has criticized NATO countries for failing to meet this target. NATO Allies agreed to submit defense spending plans by the end of 2017 that will outline their plans for achieving the 2% target by 2024. Currently, only 15 of 29 countries have announced clear plans. Although NATO faces numerous and complex security challenges, the Alliance encourages the member states to meet the political goals they have set as a means to continue to guarantee peace and security.

By Xhoana Dishnica

NATO’s greatest responsibility is to prevent conflict and maintain peace. For this reason, at the Wales Summit in 2014, the Alliance decided that all Allies should spend 2% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on defence within the next decade.[i] This plan was developed in accordance with Article 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which states, “In order more effectively to achieve the objectives of this Treaty, the Parties, separately and jointly, by means of continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid, will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.” NATO’s leaders set the 2% benchmark following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and amid civil wars in the Middle East.[ii] At the meeting, Allies that had already met the goal agreed to keep up this level of spending, while those that did not promised to reach this target. Allies also promised that at least 20% of their military spending would go towards new equipment, research, and development by 2024.[iii] In the years after the Wales agreement, NATO started to publish annual reports that show members’ contributions based on their GDP.

Source: NATO Public Diplomacy Division, “The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2018”, NATO, 2019.

According to the Secretary General’s Annual Report in 2018, only seven of 29 member states are currently meeting the recommended spending target of 2% of GDP. Despite US President Donald Trump’s criticism of NATO countries, particularly European countries, for failing to meet this target, six European countries are over the 2% threshold.[iv] These European countries are Greece, spending 2.36%, the UK, spending 2.12%, and Estonia, spending 2.08%, followed by Poland, spending 2.02%, Latvia, spending 2.01%, and Lithuania, spending 2%. President Trump has even put pressure on European Allies to reach a 4% spending target, as the United States gives special importance, and nearly 4% of its GDP, to defence spending. This was just one of President Trump’s disruptive tactics during the NATO Summit in 2017.[v]

How have European Allies and Canada performed according to the Secretary General’s 2018 report? Are all Allies making efforts to increase defence spending?

Greece

Greece exceeded the 2% goal and is ranked second in defence spending after the US. Greece has continued high levels of military spending despite the Eurozone crisis and economic difficulties in the country between 2008 and 2018. In 2010, Greece revealed a series of austerity measures aimed at curbing the deficit. The EU promised to act over Greek debts and told Greece to make further spending cuts. On 2 May 2010, the Eurozone members and the IMF agreed on a EUR 110 billion bailout package to rescue Greece. Despite five years of punishing austerity, its military budget remains amongst the highest in the EU. Greece maintains a military focus on neighbouring Turkey, which is still perceived as a threat. Tensions between Greece and Turkey are not new, but the discovery of rich deposits of liquid and gas petroleum in the Eastern Mediterranean is changing the balance of power in the region. According to critics Greece’s military spending is largely on personnel, including pensions. The country is expected to spend 12.4% on equipment and another 24% on functional expenditures in 2019.

The United Kingdom

The UK is ranked third among NATO Allies in defence spending, with 2.12% of its GDP spent on defence. As Europe’s largest defence spender, the United Kingdom’s defence budget decreased to USD 50.7 billion in 2017 from USD 52.6 billion in 2016, far below the 2014 amount of USD 65.6 billion. In 2018, however, this increased to USD 61.5 billion. In January, the British government disclosed the initiation of its third defence review, which will assess the UK’s security posture and set spending priorities. After the Brexit referendum, the government launched the National Security Capability Review to ensure that British capabilities are able to meet its foreign policy targets. After Brexit, the British engagement in NATO is expected to increase.

The Baltic States

Bordered by Russia, the Baltic States, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, see NATO membership as essential to their security strategies. Due to their weakness, the three states have rapidly increased their defence spending. Latvia’s defence budget more than doubled from 2013 to 2018, increasing from USD 281 million to USD 701 million. Lithuania has increased defence spending from USD 355 million to USD 1.06 billion over the same period. All three states have plans to meet goals independently and together, including a plan to increase air defence covering all three countries. While the efforts of the Baltic States should be applauded, a lot of these funds go toward replacing old (Soviet) equipment with modern equipment. The Baltic States are largely dependent on NATO’s enhanced forward presence (eFP) to resist an armed attack. In the future, the Baltic States would like to acquire F-35 Lightning II jets and F-16 fighter jets.[vi]

Poland

Poland’s strategic position makes it especially susceptible to Russian intervention and a possible attack. According to the Secretary General’s 2018 report, Poland’s budget has grown to USD 12.08 billion in 2018 to bring total defence spending to 2.08% GDP, ranked fifth for percentage defence spending. Poland is completing the construction for the land-based Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defence system and plans to acquire new F-35 Lightning II jets and used F-16 fighter jets from the United States. The Polish government says that they will maintain the investment level of 2% and even plan to increase the defence spending to 2.5% by 2030.[vii]

Romania

Romania has increased its defence budget from USD 2.6 billion in 2014 to USD 3.6 billion in 2018. Romania’s defence spending reached 1.93% of GDP in 2018. The government’s plan is to increase its defence budget to USD 5 billion by 2020, which would push it above the 2% target. According to NATO, the country has “legal and political measures” to achieve the target soon.[viii]

France

France dedicated 1.82% of its GDP to defence in 2018, versus 1.78% in 2017, ranking ninth out of the 29 contributors. The country plans to increase defence spending to 2% of its GDP in 2025. To support this commitment, it will spend EUR 198 billion on military programming from 2019 to 2025. At this time France will devote 1.91% of its GDP to defence spending.

Turkey

Turkey pledges to meet NATO’s 2% defence spending by 2024. The country is among the 15 NATO members with plans to meet the Alliance’s guidelines. Turkey recently increased its defence expenditure to 1.52% of its overall GDP. The country’s equipment expenditure as a share defence spending was 37% in 2017, exceeding the NATO guideline of 20%.

Germany

Germany has made little progress. The country is the weakest performer in defence spending among Europe’s top five economies. It is the lowest spender among the big three: France, Germany, and the UK. To meet the 2% target, Germany will have to spend around EUR 70 billion annually on defence. Recently, Germany announced a goal of reaching a target of 1.5% of GDP by 2024. Germany spends considerably less on equipment per military personnel than France or the UK despite having armed forces of comparable size.[ix]

Canada

Canada’s recent defence policy review “Strong, Secure, Engaged” (SSE) includes a renewed emphasis on hard power. The Government of Canada published figures in May 2018 showing that its defence spending decreased USD 2.3 billion dollars over the previous year. Figures predict further shortfalls, with the SSE promising USD 24.3 billion in spending for 2020-2021, while the Department of National Defence is planning total spending at USD 20.1 billion for 2018-2019. Defence spending only rose by USD 1.1 billion over three years from 2014 to 2017. The Canadian Global Affairs Institute has attributed the under-spending to “dysfunctional defence procurement system at Canada’s Department of National Defence”. [x]

Italy

Rome’s principal defence focuses across the Mediterranean. Italy’s defence spending decreased from USD 26.6 billion in 2013 to USD 25.78 billion in 2018. The Eurozone crisis has opened important structural weaknesses in the country, which have contributed to the decline of spending. The Italian government published a defence plan in 2017 highlighting goals to increase personnel and upgrade equipment. Italy retains a strong defence industry and remains an active member in NATO exercises, air-policing missions, and operations while also leading the EU’s Operation Sophia in the Mediterranean. As such, Italy is expected to maintain a line of continuity in defence as it is deepening involvement in key European defence projects and military operations.

Albania

Albania dedicated 1.26% of its GDP to defence in 2018. The country has the weakest economy among the Allies. In 2016, the majority of the budget went toward personnel rather than equipment, training, research, development, and infrastructure. Although the higher percentage of funds went towards personnel, which includes paying salaries and pensions, this amount was still too low, resulting in low salaries paid to military members. Albania has contributed to NATO missions in Afghanistan to help fight international terrorism, and it is also part of the increased military presence in the Baltic region, sending some troops and forces to the battlegroup in Latvia. Albania is completing construction for a new airbase in Koçovë as an added value not only for Albania but also for the region. Albania has started to invest more in defence and has declared it will reach the goal of spending 2% of GDP on defence by 2024.

At the bottom of the latest NATO report are Slovenia, spending 0.98%, Spain, spending 0.92%, Belgium, spending 0.90%, and Luxembourg, spending 0.46%.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg has met the 20% investment target and intends to continue exceeding that figure through its national defence effort. The country has agreed to increase its defence spending from 0.4% to 0.6% of GDP by 2020. Luxembourg will continue to invest in military capabilities that are relevant for the Alliance. The country has taken part in NATO military operations and deployments and will continue to do so. Luxembourg has been present for more than 15 years in Kosovo as part of KFOR and since 2013 in Afghanistan.[xi]

Conclusion

NATO Allies agreed to submit defence spending plans by the end of 2017 that will show how each country plans to meet the 2% target by 2024. Currently, only 15 of 29 countries have announced clear plans.

At this week’s London Summit on 3-4 December 2019, many NATO leaders will hope to avoid the drama over defence spending, especially French President Emmanuel Macron, who recently warned Europe that “NATO is becoming brain dead” only weeks before.

Despite plans for more unified defence spending, NATO in 2024 is unlikely to be an Alliance living in harmony. The United States will increase pressure on Europe to take more responsibility for its own security.

Although NATO faces numerous and complex security challenges, the Alliance will continue to encourage its member states to meet the political goals they have set and continue to guarantee peace and security.[xii]

About the Author

Xhoana Dishnica lives in Budapest and works as a technical support Analyst for Hewlett Packard. She is an Albanian national, born in Tirana. After studying education and translation in a master’s program organized by Sorbonne University, she focused on international relations and took several courses on the European Union. She has worked as a translator for the Albanian Telegraphic Agency (ATA), where she translated world news, politics, and economics from Agence France Press (AFP). She is fluent in English, French, and Italian. She is very interested in the politics of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and participated in YATA Germany’s NATO’s Future Seminar in 2018 in Berlin

Notes

[i] Nancy A. Youssef and Michael R. Gordon, “NATO’s 2% Target: Why the U.S. Pushed Allies to Spend More on the Military,” The Wall Street Journal, 12 July 2018.

[ii] Anthony H. Cordesman, “NATO: going from 2% non-solution to meaningful planning,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, revised 28 June 2019, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/190628_NATO_B....

[iii] NATO Public Diplomacy Division, “The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2018”, NATO, 2019.

[iv] Michael-Ross Fiorentino, “NATO pledge: Which European countries spend over 2% of GDP on defence?” euronews., last updated 14 March 2019, https://www.euronews.com/2019/03/14/nato-pledge-which-european-countries....

[v] Cordesman, “NATO: going from 2%.”

[vi] Attila Mesterhazy, “Defence and Security Committee,” NATO Parliamentary Assembly, 2018.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Romania Ministry of National Defence, “The military strategy of Romania,” Bucharest, 2016, https://www.eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/Defence-Procurement-Gatewa....

[ix] T. Lawrence and G. White, “Germany’s Defence Contribution – Is Berlin Underperforming?” International Centre for Defence and Security, Tallinn, Estonia, 11 July 2018, https://icds.ee/germanys-defence-contribution-is-berlin-undeperforming/.

[x] Mesterhazy, “Defence and Security Committee.”

[xi] The Government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, 2017.

[xii] Fiorentino, “NATO pledge: Which European countries.”