Cyber Security – A Strategic Security Priority for NATO

Today, every aspect of human life is part of cyber space, even the ones we are not aware of. This makes us all combatants, and geography becomes unimportant. Consequently, the need for strong and unified cyber security is crucial, and ‘cyber defence’ is a key aspect of this. NATO has recognised the importance of incorporating cyber defence into the Alliance’s operations; however, little has been done to turn NATO’s Cyber Defence Pledge into action. This paper considers the cyber issues most relevant to NATO and advocates for the creation of the Cyber Security Doctrine, Grand Cyber Security Strategy, and the Cyber Joint Task Force. These three suggestions are crucial for developing the policies and procedures within which the Alliance will create its cyber ‘muscle memory’ and ultimately increase its strength within the cyber domain so that NATO’s cyber defences are equal to its defences in the air, on land, and at sea.

By Petra Cicvaric

INTRODUCTION

Carl von Clausewitz provides one of the most comprehensive definitions of war. As Clausewitz understands it, war is “an act of force (violence/power/control) to compel our enemy to do our will.” In this sense, wars are usually perceived as violent and bloody. Following years of bloodshed in successive world wars, NATO was established 70 years ago in order to combat these (largely physical) acts of force and has been responsible for collective defence, crisis management, and cooperative security ever since. However, since the 1980s concerns about virtual, encrypted cyber ‘evil’ have interested and concerned both military and political minds.

Today, we are living in an e-society within which almost all services—from media and shopping, communications and banking, to security services—are operated online in cyberspace. This overreliance on technology and the cyber domain increases the security stakes both for states and civilians. According to NATO, the number of state-sponsored cyber interferences on the Alliance’s, member states’, and partners’ infrastructure has been on the rise in recent years. The examples span from Estonia in 2007 to Ukraine in 2014, to more recent operations like the Fancy Bears attack on the UK.

These attacks suggest that the cyber threat landscape is developing faster than NATO’s strategy against cyber attacks. It would be an understatement to say nothing has been done in order to reduce this gap; yet, the Alliance is still not fully ready to face digital threats and react to them. In order to confront these issues and put an end to the escalation of conflict, the Alliance needs a hierarchical cyber strategy and closer collaboration with its partners. Finally, NATO needs not only to update the content of Articles 3 and 5, but also to create smart defence ‘muscle memory’. Cyber attacks still tend to utilize the means of conventional warfare, despite NATO’s tendency to view cyber as a hybrid or asymmetrical threat. Therefore, this essay recognises NATO’s recent efforts made to fulfil the Cyber Defence Pledge, but it also stresses the importance of increasing the pace and the efficiency of these changes in order to fully treat cyber as any other means of conventional warfare.

CYBER AND ITS IMPLICATIONS

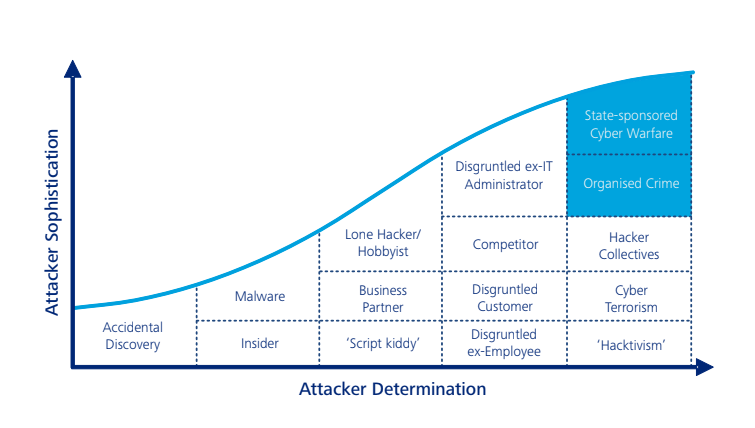

Cyber security is usually perceived and defined from a purely technological standpoint. It has yet to be fully legally, strategically, and operationally defined. As a result, it has become an attractive subject for academics and professionals. Cyber is an example of the non-physical battlespace, within which cyber attacks are becoming increasingly intense and complex, reflecting fast technological advancements, e.g. quantum computers. Moreover, cyber attacks annihilate the concept of critical geopolitics, since they are not constrained by borders, distances, and topography. In addition, they equalize combatants and non-combatants by targeting military, civilian, and dual-purpose infrastructure. Cyber attacks can also lead to human casualties. Therefore, cyber security needs to be perceived as an existential threat with destructive capacity rather than a hybrid or asymmetrical one. Moreover, it is important to stress that cyber is a relatively new but fast-developing domain within which participants are using a variety of techniques in order to achieve their end goals (see Figure 1). This makes it harder to regulate, and therefore, it represents a key area of ‘grey-zone’ challenges and an important element of battlespace management.

Figure 1: Graphical illustration of Actors and Attacker Determination

NATO’S RESPONSE

One of the main reasons why NATO is the most successful security alliance is its ability to rapidly adapt to the changes in political and security environments. One of the key aspects of this adaptability is NATO’s ability to update its strategic foundations.

NATO’s adaptability was seen in two recent cases in 2014. First, after European security was significantly altered when the order between West and East was jeopardised by Russian aggression in Eastern Europe, namely Ukraine. Second, when the Middle East was shaken by civil wars and Islamic terror in Iraq and Syria. NATO was surprisingly quick in its response to the issues in these regions, together with its allies. The Alliance managed to improve its defence capability within the same year and enhance its defence policy two years later, in July 2016 at the Warsaw Summit, by reflecting the new threats in the South and East.

Recognizing the importance of maintaining e-safety, NATO incorporated cyber into Article 5 of the Washington Treaty and adopted the Cyber Defence Pledge in the context of Article 3, which states, “Allies will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.” Consequently, cyber has become NATO’s newest operational domain, and Allies have committed themselves through the Pledge to enhance their national defences in cyberspace, foster cyber education, enhance skills and awareness, etc. Despite this great improvement there are some drawbacks to both advancements that prevent the Pledge from turning into action.

First, Article 5 states that a cyber attack on one or more Allies must be “significant”’ for the article to be invoked. According to officials, this deliberate ambiguity of defining parameters should discourage hostile operations to fall just below the threshold, or being considered ‘significant’. The main argument behind this reasoning is that this approach gives Allied forces more space for manoeuvre. However, since there is no clear standard for defining and measuring cyber attacks applied across the Alliance, the metrics and responses to what constitutes a ‘significant’ attack vary among member states. As a result, it is challenging to compare data from different national security contexts. Consequently, the hypothetical invocation of Article 5 over a cyber threat and Allied responses to the rapid and ever-expanding threat landscape would likely be slow and uneven.

Many cyber attacks are not severe enough to cross the imaginary threshold to invoke Article 5 or to result in armed conflict. It is indeed questionable if a clearly articulated threshold would even deter state or non-state actors from crossing it. How do we then measure the significance of a cyber attack, especially as all cyber attacks have the capability to be highly damaging, disruptive, and destabilising if the right infrastructure is attacked? Moreover, how does NATO, as a security alliance, then decide what is a proportionate and effective response when we do not have a unified definition and strategy?

Secondly, due to the cross-cutting character of cyber security, national cyber security strategies often run the risk of failing to address all cyber security requirements of national institutions. For that reason, many national cyber security strategies highlight the importance of generating institution-based cyber security strategies. These strategies should envision precautions for already existing problems while providing guidance on how to tackle future challenges.

It is worth mentioning that the development of these procedures is much more complex and dynamic than just the pure establishment of certain rules across markets and socio-economic sectors. The modern cyber domain affects all sectors, including the abovementioned but also the military, media, and government. As a result, more targeted and specified procedures are required in order to ensure that the sense of safety can be applied across the Alliance.

Government institutions, militaries, private, and public companies as well as academia and civil society must develop a cooperative approach and Grand Cyber Security Strategy. This strategy would provide an understanding into how to analyse data from all sectors and apply that knowledge accordingly. Such common strategies would increase the operational potential of all institutions involved. One recent example of this is a new cyber security centre in Mons, Belgium, which was created in response to the decision made among the Heads of States and Governments at the Brussels Summit in July 2018.

In order to develop the Grand Cyber Security Strategy, the Alliance does not necessarily need to build new bodies and create new policies. On the contrary, it could use already available resources such as Allied Command Transformation (ATC) and/or the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (NATO CCDCOE).

Once the global framework for cyber security is established and the aims and objectives outlined, the Alliance can agree to standardized management and operational control, as well as to where exactly it is to be applied. Such an accomplishment would aid NATO’s technological advancement and ensure that Allied forces can successfully respond to modern global issues.

NATO IN THE CYBER CENTURY?

The security environment in 2019 is simultaneously symmetrical and asymmetrical—or, as some like to call it, militarily and politically hybrid. Human capital seems to be limited in modern conflict due to technological advancements; however, this technology also makes us all combatants, and daily life becomes a war zone. Cyber is opening new fronts, and it is not so simple to determine what, where, and how these fronts will be under attack. That is why we need to address the need for an updated approach to these threats.

NATO should not only be able to defend itself but also deter interferences in the cyber world. Modern technology is constantly evolving and becomes increasingly vulnerable to new, malicious interferences. The number and range of devices connected to each other and the internet is exponentially growing and creates new threats to not only data privacy but also to the physical security of every individual. Therefore, more clear-cut agreements to streamline and regulate offensive cyber operations within the Alliance may be needed, since member states are currently struggling to find a middle ground in terms of burden sharing and threat perception.

Up until now we have always addressed what NATO should do based on its three core tasks (collective defence, crisis management and cooperative security). But, we have not discussed how NATO can meet them. In other words, we must identify the full spectrum of ends, ways, and means, because where we are now there is not a clear, common agreement on NATO’s end goals.

In order to attain successful and effective tactics, one must develop a sophisticated set of strategies and methods. Recognising this, the Alliance has developed an innovative approach called Smart Defence. This method should ensure stability, sustainability and growth by focusing on efficiency and efficacy. In order to reach resilient smart defence in the cyber domain, the Alliance must work on the establishment of e-centric cyber methods. By attaining this, NATO will be able to secure its virtual space, secure and protect its infrastructure, and provide defence and cooperation.

However, similar to conventional warfare, it is not enough to integrate the processes and procedures needed for planning and conducting joint operations. In order to further strengthen the alliance within the cyber domain, it is of extreme importance to educate, train, and exercise cyber defence in order to create something like ‘muscle memory’. With the sophistication of the arms and variety of techniques across the Alliance, it is crucial to work on reducing the disparity between member states’ cyber capabilities. Ideally, NATO will be able to establish a ‘Cyber Joint Task Force’ and be able to engage in joint operations. In order to reach this, the Alliance will have to speed up the creation and indoctrination of the Cyberspace Operations Doctrine and Grand Cyber Security Strategy.

This process can be traced through six steps:

sound strategic structuring and planning;

operational coordination in exercises and in the field;

specialization of force structure, command, and operations;

achieving collective defence through collective efforts;

burden sharing;

technological advancements, considering the threats and challenges of the twenty-first century.

Whilst working on the implementation of the Cyber Defence Pledge through doctrine and strategy, the command will be under national jurisdiction and might be provisionally supervised by the ATC and NATO CCDCOE.

Moreover, on the strategic level NATO could also work on creating a database of the Allies’ and partners’ cyber capabilities and vulnerabilities in order to share concrete knowledge-based information on security affairs in the cyber domain. By doing so, it will enhance cooperation amongst Allies and partners, as well. This will greatly benefit the Alliance in preventing electronic warfare, detection of attacks, and reaction to them; but, most of all it will avoid the duplication of efforts.

One of the most successful examples can be found in the EU and its improved cooperation with NATO. A technical agreement between the EU’s Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-EU) and the NATO Computer Information Response Capability (NCIRC) allows for faster and better information exchange between both organisations during incidents such as the Wannacry and NotPetya cyber attacks. This was done through the Technical Arrangement on Cyber Defence, concluded in February 2016, which facilitates cooperation at the operational and tactical level.

In addition, NATO should allocate a budget for cyber security in order to meet all the technological necessities of the Alliance. It would be advised for the Alliance to continue developing Cyber Rapid Reaction teams that can always be on standby to assist Allies.

Lastly, reflecting on the issues discussed at the beginning of this essay, NATO’s capability and capacity to operate in the digital world should be clarified. To date there has been little public discussion within NATO on what role, if any, international law should play in governing either offensive or defensive cyber actions. There are few treaties or UN statutes that deal explicitly with cyber actions. Therefore, the creation of a cyber jus ad bello and jus in bello should be explored, since NATO still has not managed to find a suitable answer to the question of how and under which conditions NATO would respond if a member state were to invoke Article V of the North Atlantic Treaty following a cyber attack.

CONCLUSION

Clausewitz’s assertion that “war is an act of force” should guide the discussion about cyber security as one of NATO’s strategic security priorities. The possibility of a cyber war has been discussed both as the future of warfare and as an exaggerated threat. It might be too early to tell which of the two currents is correct, but it is evident that setting out NATO’s tasks without reflecting on how to approach cyber security is counterproductive.

The reason why Clausewitz’s definition of war is still relevant, despite the debate of whether or not it is possible for countries to engage in cyber warfare in the traditional sense of war, is because there are so many different ways of reading it. Cyber warfare does not necessarily entail physical force, but it can lead to it, like we have seen in the examples of Estonia, Georgia, and Ukraine, among others. Moreover, it can be argued that cyber capabilities are a manifestation of power and aim to impose control over the enemy in order to compel them into a win/lose situation.

As previously discussed in this essay, it seems that NATO has recognized this analogy and started working on establishing effective cyber defence. However, for this aim to be achieved, member states and partners must foremost treat cyber as a conventional threat and work together to create a ‘Cyber Grand Strategy’ and develop cyber ‘muscle memory’. If NATO wishes to remain a crisis management institution and security alliance, it needs to create sustainable, agile, and limitless policies together with specialized military and civilian installations that will implement the Smart Defence methodology.

Only when all of these steps are followed, and member states and partners see and understand cyber attacks in the same manner, can we aim to clarify the rules of engagement for cyber warfare within international law. Only then will NATO have full control over the cyber domain like it has now over air, sea, and land.

Petra Cicvaric is a postgraduate student working toward an MA in War Studies at King’s College London. She has published articles dealing with the impact of BREXIT on NATO and on utility systems as sources of political power through the lenses of NATO and IoT. Her undergraduate dissertation examined hybrid warfare in the case of Eastern Ukraine and Crimea. She has worked in the European Parliament as a trainee. Her main areas of research are security and defence studies and international relations.